Chicago, Illinois, is a city with a deep division over public art. A case in point: The city’s controversial “Graffiti Blasters” abatement program, which for the past 21 years has criminalized street artists and muralists, by linking aerosol expression of any kind with gang violence.

Chicago, Illinois, is a city with a deep division over public art. A case in point: The city’s controversial “Graffiti Blasters” abatement program, which for the past 21 years has criminalized street artists and muralists, by linking aerosol expression of any kind with gang violence.

Introduced in 1993, the same year as the classic hip-hop albums “Midnight Marauders” and “93 Til Infinity,” Graffiti Blasters – the name sounds like a lightweight racist take on the term “ghetto blaster” – became a jump-off for anti-graffiti measures as a public policy point. GB ushered in a wave of anti-graffiti initiatives in cities like New York, Los Angeles, San Jose, Pittsburgh, Denver, Milwaukee, and Houston, and became a model for similar programs in several major world cities. Indeed, it could be argued that the modern abatement industry – currently a $20 billion industry – traces its beginnings back to Chicago’s anti-graffiti initiative, reportedly a pet project of former Mayor Richard J. Daley.

Poor communities of color have been subjected to a universal coat of dull brown paint as a failed solution to graffiti vandalism.

Graffiti has been a hot-button political issue in Chicago ever since. It’s also been a goldmine for city abatement crews. Over the past two decades, the city has funneled hundreds of millions of dollars into abatement efforts – which totaled $9 million in 2010 alone, or more than $3 for every Chicago resident, despite having a $700 million budget deficit at that time. Chicago’s over-the-top attack on the aerosol aesthetic has included the banning of the sale of spray paint through the city, criminalizing legitimate aerosol artists in the process. As CRP founder/Executive Director Desi Mundo says, “No other artistic medium has been targeted in such a comprehensive manner.”

What the city has received in return for those efforts has been a matter of debate. While the 311 anti-graffiti hotline is often cited by aldermen and the business community as an effective tool for urban blight reduction, wait times of 30 days or longer have been recorded, even though the hotline promises graffiti removal within 24-48 hours.

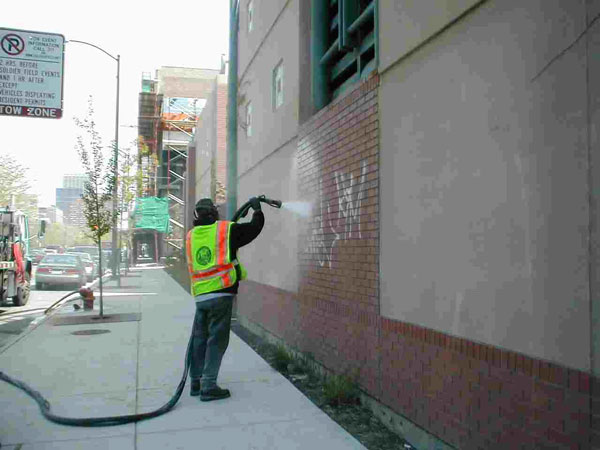

Pressure washing graffiti has been Chicago’s more costly alternative for removal. Yet is has been applied selectively in more affluent communities.

More tellingly, no permanent graffiti reduction has yet been achieved, despite these efforts. Even law enforcement has been skeptical about the cost-effectiveness of abatement; in 2011, Sheriff Thomas Dart proposed saving $600,000 in funds for the cash-strapped city by eliminating the suburban anti-graffiti unit, but the Cook County board rejected the proposal.

Ironically, another impact of the relentlessness of the buff has been to develop Chicago’s skilled aerosol writers. As the New York Times noted in 2011, “the anti-graffiti strategy — deploying crews called graffiti blasters to quickly erase or blot out painted surfaces — has imposed a kind of natural-selection process in the graffiti subculture. By discouraging all but the shrewdest and most determined practitioners, the city and county have inadvertently contributed to making Chicago a vibrant hub of graffiti activity.”

Furthermore, Chicago’s collapsed financial status – its 2014 deficit is still almost $340 million – has led to an increase in urban blight. Yet the most visible result of the city’s one-sided approach to blight mitigation has been the brown paint applied uniformly for miles across Chicago’s low-income, inner-city communities, which has been cited as a cause of depression.

The importance of bees as pollinators in the garden cannot be overstated.

While abatement spending continues to be prioritized, since being elected in 2011, Chicago mayor Rahm Emanuel slashed the public art budget by more than 85 percent, even as hundreds of thousands in funds allocated to public art projects remain untapped. Approved public art projects include murals in schools and police stations – the latter not exactly the most welcoming place for an aerosol artist. Making matters worse, recent budget cuts which forced the closure of more than 50 schools also devastated public school art programs; more than 150 art teachers were laid off in 2013, according to the Chicago Teacher’s Union.

For all those reasons, it is indeed news when a community mural painted by aerosol artists helps a Southside neighborhood win a national competition for “Neighborhood of the Year,” an annual award given out to collaborative projects which beautify and revitalize a neighborhood and build community.

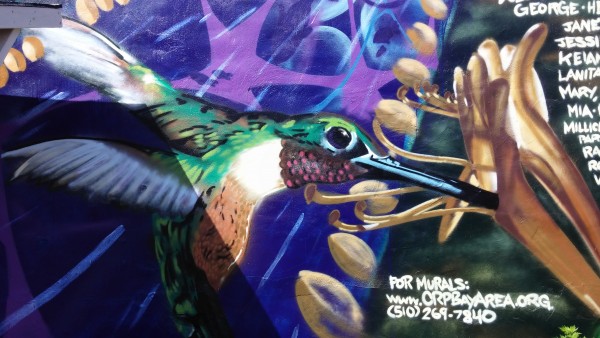

Mundo and his mentor Lavie Raven painted the original mural, located at 75th and Coles on Chicago’s South Side, in 2013. The mural was the centerpiece of a community garden project, organized by the South Shore Sustainability Collective. As Mundo notes, “The garden is run entirely by local volunteers in a location that was notorious for crime just a few years prior.”

The mural had deep spiritual significance, referencing a drummer creating the heartbeat of life; the third eye representing universal consciousness; the African concept of Sankofa, which maintains, “”It is not wrong to go back for that which we have forgotten”; Ibis birds, a symbol of Thoth, the Kemetic god of knowledge; pyramids and double-dutch jump ropes; lush, abundant greenery; and the words, “May Peace Prevail in the Universe.”

The original mural in the east garden of 75th and Coles was destroyed less than a week before the second mural was painted.

“The mural was intended to accentuate the transformation of an abandoned lot into a community garden,” Mundo says, noting that the Audubon Society, who helped to establish a migratory bird sanctuary at the site, is one of many organizations who have gotten involved with the project.

Unfortunately, the mural was destroyed by the property owner after it was damaged, just two weeks before the competition winner was announced. However, the judges recognized the significance of the mural and its contribution to community redevelopment efforts and awarded the prize to the South Shore Sustainability Collective anyway. A companion piece next to the destroyed mural called “Mama Garden” – which continues the nature theme with fruits, birds, butterflies, and rivers – has since been painted by Mundo, and there are plans for him to redo the destroyed mural.

Hummingbirds are also important pollinators that the garden hopes to attract.

Mundo maintains the South Shore murals show the “immediate and powerful” impact of a community-based approach to public art. He compares such efforts with the lackluster state of public arts in Chicago and says the money allocated to failed anti-graffiti attempts would be much better spent by promoting public mural efforts which benefit underserved communities. “As Emanuel slashes funding for schools, youth services, and arts programs, youth are pushed to express their creativity through other means,” Mundo explains.

A record of disproportionate spending hints at the larger issues around graffiti and public art in Chicago. Public art funding in 2014 has dropped to $50,000, or one-eighth of the approximately $4 million spent annually on Graffiti Blasters. And while zero-tolerance advocates speculate that buffing over gang tags decreases the threat of street violence, no data conclusively links abatement efforts to violence reduction in Chicago. It is a fact, however, that legal, sanctioned murals have been caught up in the tide of brown paint by overzealous abatement crews, illegally buffed at the behest of art-hating aldermen. With no end to the graffiti epidemic in sight through costly-yet-ineffectual institutionalized abatement methods, the South Shore mural’s success suggests it’s time to consider a more holistic approach.