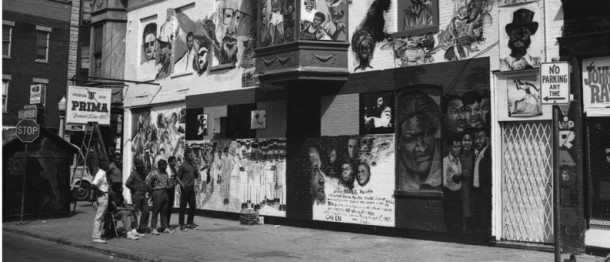

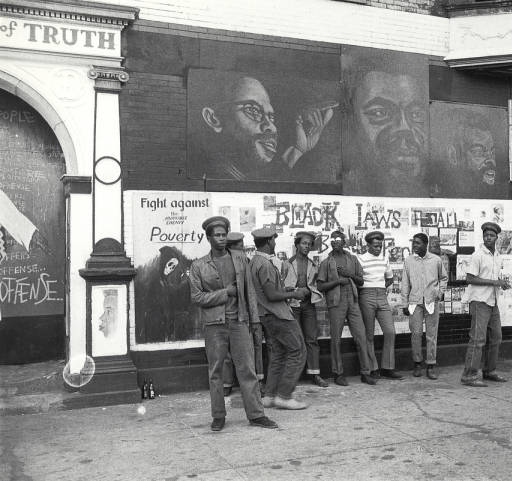

The Wall of Respect (photo courtesy Block Museum).

There’s an old saying: respect isn’t given, it’s earned. That maxim is especially appropriate in telling the story behind one of America’s most-celebrated murals. But to tell that story properly, it’s important to trace the historical context which led to its creation, outlining the connections between social justice movements and creative expression, as evidenced by two major urban cities: Chicago and Oakland.

Lorraine Hansberry

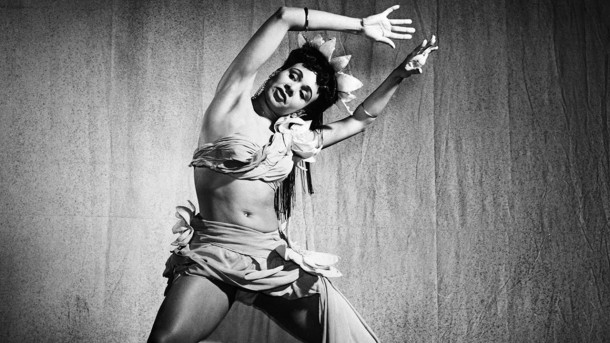

In the 1930s, Chicago was the center of the Black Renaissance , an African American creative movement which emerged out of a neighborhood known as the “Black Belt” in the city’s South Side. Originally a literary movement identified with Richard Wright, Gwendolyn Brooks, and Lorraine Hansberry, the movement’s parameters expanded during the 40s and 50s, as Chicago’s population swelled with tens of thousands of black families who migrated from the Jim Crow South. Eventually, the Black Renaissance became associated with black consciousness and cultural pride, as well as with other artistic disciplines: music, theater, dance, visual arts. Some of the famous names which came to be associated with the movement included jazzmen Tommy Dorsey and Louis Armstrong, and Katherine Dunham—the godmother of African dance in America, and a major influence on the Afro-Diasporic arts movement which flourished in Oakland in the 70s and 80s.

Katherine Dunham

Oakland’s black population also experienced migratory waves of people fleeing the racist South, beginning in the 1940s and continuing up until the 90s. Oakland’s black population tripled between 1940 and 1950, and nearly doubled again in 1960 (eventually peaking at 47% in 1990). In the immediate aftermath of the Civil Rights Movement, Oakland became a mecca for progressive African American activism – influenced by, but not limited to, the direct action practices of SNCC and SCLC, as well as by the radical militancy of the Black Power movement.

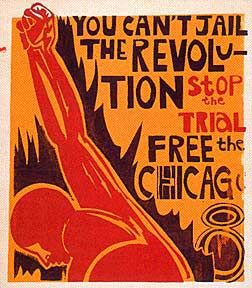

A political poster for the Chicago 8

The late 60s and early 70s were a time of cultural upheaval and social change across America, marked by protests against the Vietnam war, as well as protests against the unofficial war being waged on the black community by the federal government and local law enforcement. As Jeff Chang points out in “Who We Be,” cultural wars were also happening at this time, between the right-wing conservatives, and the left-wing counterculture. Perhaps unsurprisingly, these protests, led by community activists, coalesced into full-fledged social justice movements in which revolutionary art was upheld as a form of communication as well as propaganda in the literal sense.

It’s also no surprise that Chicago and Oakland share many commonalities. Both cities are known for their gritty, working-class aesthetic and ethnic diversity (despite Chicago’s segregation). Both experienced a mass migration of African-Americans from the South and became cultural fountains for black expression. Communities of color have made up the majority of both cities’ populations, but have also been historically under-represented within political power structures and subjected to economic inequity, such as racially-restrictive covenants and urban renewal policy which created inner-city projects – all while being targets for societal discrimination and police violence.

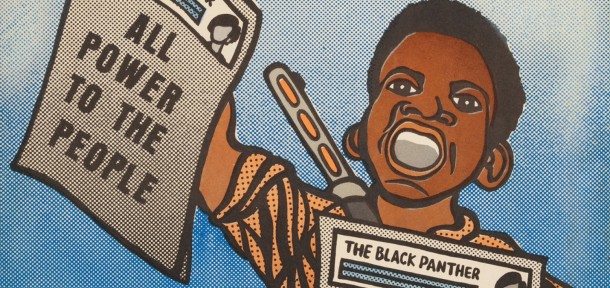

Art by Emory Douglas

Douglas’ art – not to mention the popular graffito slogans “Free Huey” and “Power to the People”—were among the influences on African American artists in Chicago, who had taken a page from their contemporaries in NYC and Oakland and formed artists’ collectives promoting new themes intertwining liberation struggles with cultural pride.

In 1967, one year after the founding of the Panthers and two years after the inception of the Black Arts Movement, one such collective, the Organization of Black American Culture (OBAC) —whose acronym, pronounced oh-bah-see, is also the Yoruba word for “chieftan”—came together to paint a guerilla-style mural in a poverty-stricken, drug-infested neighborhood in the middle of gang turf on Chicago’s South Side.

The Wall of Respect. Photograph by Robert Abbot.

The mural, which has since come to be known as the “Wall of Respect” (WoR), spearheaded a community mural movement in Chicago which continues to this day. ,in addition to frescoed art painted directly on the wall’s surface, there were painted canvases—more than 50 portraits in total—to which photographs and inscribed poetry were added.

The Wall originally honored black heroes—blues and jazz players, statesmen and political activists, sports figures, authors, dancers, and religious leaders. Among those depicted were Stokely Carmichael, Adam Clayton Powell, Paul Robeson, Malcolm X, Marcus Garvey, H. Rap Brown, Elijah Muhammad, Aretha Franklin, Muhammad Ali, and Gwendolyn Brooks.

The selection of images was controversial, reflecting ideological differences within the black community. Dr. King was omitted from the wall after objections from local clergy (too radical for them) and SNCC members (not radical enough); Elijah Muhhamad himself complained about being on the same wall as Malcolm X, and was replaced by Nat Turner. Over time, other sections were whitewashed and repainted with new images, among them a Black Power first, depictions of the KKK and police brutality, and local community organizers.

Fred Hampton

The mural appeared at a particularly turbulent time in Chicago’s political history – which often played out in the streets. In 1968, there were riots following the assassination of MLK, and anti-war protests during the Democratic National Convention; Black Panther co-founder Bobby Seale was among eight defendants charged with conspiracy and inciting riots. In 1969, six people were shot by police and hundreds arrested during the “Days of Rage,” a series of direct actions by radical leftist group the Weather Underground. A month later, two cops and one Panther were killed in a gun battle which also resulted in nine policemen being shot. A month after that, Hampton was murdered in his sleep during in a police raid which was later discovered to be a covert, FBI-directed, assassination. 5000 mourners attended Hampton’s funeral, a civil rights lawsuit was filed (eventually settled for $1.85m), and the Weather Underground bombed six police cars in tribute to their fallen comrade.

During this time, the WoR continued to be a magnet for black community organizing, cultural events, and political activism on the South Side (much like Oakland’s DeFremery Park). The mural was written up in local papers, and local kids conducted impromptu mural tours for visitors. The site also reportedly attracted the interest of undercover cops and FBI agents; artists received anonymous phone calls and threatening letters. Sadly, the building on which the mural was located, which had been targeted for urban renewal, burned down in a suspicious fire, and was razed by the city in 1971.

The Wall of Truth

The WoR inspired other pro-black and socially-conscious murals throughout Chicago, leading directly to the establishment of several muralist organizations, including the Community Mural Project and the Chicago Mural Group. Murals soon began to proliferate in other major cities, including Philadelphia, St. Louis, San Francisco, Los Angeles, and Boston. The Respect mural also paved the way for other works by William Walker, one of the lead artists on the original project, who took on the role of keeper of the Wall after the OBAC visual artist collective split into two factions.

Amiri Baraka

These works included the “Wall of Dignity,” painted in Detroit in 1968, and the “Wall of Truth,” a darker, more defiant work painted across the street from the WOR, on the side of a fire-damaged building which also housed a drug clinic and daycare center, in 1969. The Truth wall was harder-edged and less-ambiguous than its companion piece – a reflection of the perilous times. It featured homages to Hampton, Malcolm X, W.E.B. DuBois, and LeRoi Jones (Amiri Baraka) – a cofounded of the Black Arts Movement.

Despite the more-political tone, it too became a community treasure. In 1971, after the building was slated for demolition, community pressure delayed the destruction until the mural’s canvases—more than 35 of them—could be relocated, to Malcolm X College.

Along with Walker, other artists identified with the two Walls were Caryl Yates, Astrid Fuller, Sylvia Abernathy, Donald Lee, Wadsworth Jarrell, Barbara Jones, Myrna Weaver, Norman Parish, Edward Christmas, and Eugene Eda. Both Walls were said to be owned not by the individual artists who painted them, but “belonging to the community.”

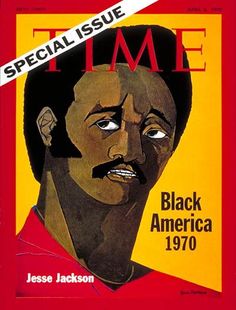

A 1970 Time magazine cover

A 1970 Time magazine cover story on black America, which featured the WoR, attracted attention to Chicago’s street art scene; in 1971, the mural movement got its first taste of recognition in the mainstream art world, when the Museum of Contemporary Art featured an exhibit called “Murals For the People.” By the end of the year, more than 60 mural had been painted in Chicago.

Walker and Eda remained prolific throughout the 70s, inspiring other Chicago muralists like Justine De Van, whose “Black Women Emerging” was painted on the South Side in 1977. That same year, the first full-length book on street murals, “Toward A People’s Art: The Contemporary Mural Movement” was published, and a collective of African American artists in Oregon began painting murals centering around black life in the Pacific Northwest. (See the Block Museum’s timeline of events here.)

In 1979, Eda’s “Cultural Mural (Dedication to the Wall of Respect)” was completed on a community center built on the site of the WoR, although not without a fight – the city reportedly wanted a fountain installed instead, but community pushed back.

The WoR had finally earned its title. Although no longer present in physical form—most of its panels were destroyed in the 1971 fire—it lives on in community memory, and in the thousands of murals it inspired.

Detail from “Black Women Emerging”

A 1997 article commemorating the WoR’s 30th anniversary noted that as many as several hundred visitors a day marveled at its shrine-like wonder, and it was given near-sacred reverence by local street gangs, who bestowed sanctuary status on it, declining to exert territorial rights.

The article goes on to contextualize its impact as “a landmark mural that galvanized a south-side neighborhood and sparked a ‘people’s art’ movement that quickly spread to other cities. Soon public murals were embraced in America as socially relevant art.”

Indeed, Chicago’s community mural movement coincided with the emergence of the modern graffiti movement in Philadelphia and New York—underground subcultures which, like Oakland and Chicago, found their artistic voices in expressing messages born out of inner-city life, strife, resistance, and resilience. It also helped give rise to the notion of community-based art lending a sense of cultural identity and attachment to place, long before the term “creative placemaking” came into vogue in public art circles. Perhaps the most revolutionary aspect of this movement was the notion of collective ownership, of art created by and for the people themselves – which all started with the WoR.

Malonga Casquelourd portrait by CRP, detail from “The Universal Language”

50 years after its creation, the WoR has transcended its original context and become part of American folklore and contemporary art history. It’s been immortalized in journalistic and academic articles and—ironically, considering its origins—been the subject of museum retrospectives, in addition to influencing several generations of muralists and public artists. Its significance lies in not just its relevance to the black experience in America, but also to the evolving appreciation for murals and public art which is rooted in community. The aesthetic of art integral to the neighborhood it is located in remains central to CRP’s approach to murals.

Respect.

In Part Two of “Legacies of Respect,” Desi Mundo breaks down his recent trip to Chicago, where he was invited to present as part of a University of Chicago symposium for the Wall of Respect’s 50th Anniversary.