Community members showed up to defend Oakland’s arts and culture

As CRP previously reported, the September 3 kick-off of the public engagement phase of the Downtown Oakland Specific Plan (DOSP), followed the same week by a SPUR report outlining “big ideas,” raised community concerns about displacement and exclusion. None of those ideas, it seemed, addressed displacement, affordability, or maintaining diversity, and arts and culture seemed an afterthought at best. A second meeting, held October 19, did little to dispel those concerns.

The evening began with a speak-out to defend Oakland’s arts and culture organized by the Oakland Creative Neighborhoods Coalition, which brought together affordable housing activists, #Black Lives Matter representatives, members of black church groups, artists, justice advocates, and musicians.

OCNC’s slogan #KeepOaklandCreative in effect

Following the rally, many attendees entered the Rotunda Building where the event was being held, including CRP Executive Director Desi Mundo. In his recollection, here’s what happened next:

“There were around 20 tables with people sitting around them and the developers were giving their presentation about statistics around downtown. It was extremely quiet, compared to the passion of the community outside. I grabbed a #KeepOaklandCreative sign and stood at the top of the stairs. People were occasionally glancing back, especially when the door opened, and I could tell that they were nervous about the protesters coming in. Finally the speeches ended and the participants were asked to discuss maps and photos on the table to talk about what needed to be added and removed, and what aesthetics they liked or disliked.

“I joined a table with developers and the temporary director of the public art program. I started writing messages around cultural equity in the process, protections for existing residents and cultural institutions and the need for more public art. The developers had a facilitator at the table and I began discussing the process with them. I brought up the exclusion of the artists from the invitations, the need to reach out to the community rather than expect us to come to them, and the need to engage established arts leaders and culture keepers. These statements were reflected in what I had written down. While the facilitator feigned interest, none of my points made it into the recommendations when he presented back to the larger group.

“While we were at the tables, the community members entered the meeting singing and chanting. Chaney Turner, a BLM organizer, took over the microphone and began to bring up the concerns the OCNC and the other organizations have. The response was to turn off the microphone. The community then did a mic-check and began to shout out her points to the groups at the tables. Afterwards, community members began talking directly to the developers and engaging folks at the tables.”

This action was necessary, Mundo says, because “The (DOSP) community engagement process has been flawed from the beginning. Artists have been left out of the conversation and silenced when they attempt to engage the process.” This is troublesome, he adds, because any significant development downtown could have a vast impact on public art and the ability of artists to create a sustainable future. Artists are already being displaced from art spaces due to rising rents, and new murals could be all but eliminated by ground-level parking garages proposed for high-rise development projects. Meanwhile, Oakland’s percent for art ordinance remains in legal limbo due to a lawsuit filed on behalf of developers, and the City Council has still not spent the bulk of the $400,000 it approved in 2013 for abatement murals.

Chaney Turner of #BlackLivesMatter addresses the crowd

“This massive expenditure of resources to develop downtown seems to be coming at the expense of the other areas of Oakland which are still being neglected,” observes Mundo. “We can’t even get our City Council to spend the abatement funds that it allocated itself, so there’s no guarantee of an equitable process for future arts projects. And our Cultural Funding Department is so woefully understaffed, that even if the funds were available, the bureaucracy would still take months to actually get these projects going.”

Perhaps not coincidentally, the DOSP and the SPUR report arrive just as the SF Art Commission (SFAC) has released a survey which confirms anecdotal evidence of artist displacement. As KQED reported, “The survey found that over 70 percent of the respondents had been or were being displaced from their workplace, home, or both. As for the 30 percent that weren’t being displaced, potential displacement in the near future was a common concern.”

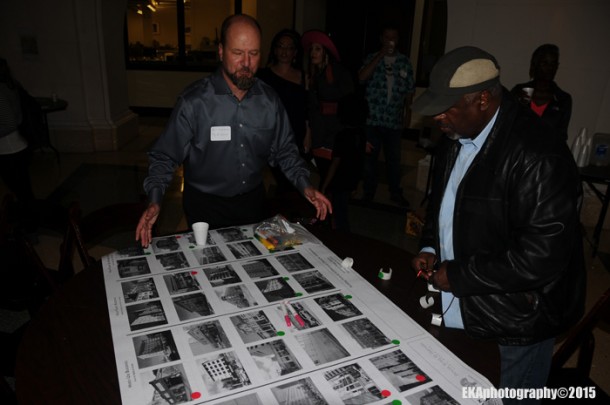

Inside the Rotunda building, planners mapped downtown’s future

The SFAC report has obvious implications for Oakland, which has the highest number of artists per capita of any city in the country, according to the city’s website. As KQED noted, there’s a direct correlation between displacement and development: “the most common reasons for artists losing their leases on workspaces and homes were business-related: building conversion, rent increases, new owners and/or owners moving into the space.”

Artists have reason to be wary of the DOSP; the Oakland Art Murmur galleries recently issued an action alert, which revealed the impact of the Broadway-Valdez specific plan (which preceded DOSP) has been to threaten them with displacement: “Many (galleries) are vulnerable right now to rapid development in their neighborhoods. These changes, if left on their own course, could mean the death of our Oakland commercial art scene.”

Inside the Rotunda building, planners mapped downtown’s future

Specifically, OAM noted, the 25th St. strip of galleries are in danger of losing their leases to a developer who plans to build market-rate housing which “will lead to an increase in rents and more galleries forced to move to an unknown destination.” If the Art Murmur galleries—as symbolic a representation of Oakland’s rebranding as there is—are forced to vacate Uptown, the neighborhood they made internationally-known, what does that say about Oakland’s commitment to culture, and the future of arts downtown?

There is a glimmer of good news in all this, however. Community calls for cultural protection ordinances to protect churches, community spaces, and public drumming have resulted in Council President Lynnette Gibson-McElhaney declaring “Protecting Oakland’s rich diversity is priority #1” and announcing her intention to “protect cultural institutions and establish an Arts & Culture Commission giving artists a seat at the table of defining the future of our beloved town.”

What’s missing? Cultural equity

Gibson-McElhaney’s statement shows that perhaps there is some political will at City Hall to resist the onslaught of the gentrification nation of developers, techies, and hipsters. It certainly reflects a response to a rising tide of community sentiment which has started to take the form of direct action, and seen a uniting of like-minded organizations and individuals into an ad hoc coalition.

Yet it remains to be seen whether Gibson-McElhaney’s cultural protection initiative will win support from the full Council, and whether the Council can work with the Planning Commission to create affordable artist housing and preserve artist spaces which currently exist in downtown.

CultureStrike’s Favianna Rodriguez confronts Rachel Flynn, Oakland’s Director of Planning and Building

It also remains to be seen what an Arts & Culture Commission would look like – whether it will take an active role in arts advocacy, promoting a cultural equity framework, and leveraging cultural capital with regards to economic development, or whether it will ultimately amount to little more than lip service and business as usual, as was the case with the previous commission.

In a best-case scenario for public artists, a restored Arts & Culture Commission would seed projects and work with city departments to develop intersectional programs like the Street SmARTs program jointly developed by SFAC and the Public Works department), work with the City Council to fast-track projects, and greatly expand the public art program — perhaps taking a cue from Los Angeles, whose City Council recently allocated $750,000 to restore fading murals and commission 15 new projects. Public art should also be maximized and integrated fully into development plans not just for downtown, but throughout the entire city – addressing blight while engaging community. Above all, development without displacement must be the city’s motto if it is to retain its “special sauce.”

In and of itself, an Arts & Culture Commission will not slow gentrification, and with displacement already taking place, may end up benefitting the “New Oakland” unless additional steps are taken, including a comprehensive Arts Master Plan, a fully-staffed Cultural Arts Department, and a revising of the public art ordinance to be more community-friendly. Community pressure appears to be working, however, and the establishment of cultural arts advocacy groups like #SoulofOakland and the OCNC represent hopeful signs that Oakland is not going down without a fight. More members of the creative arts community need to get involved, and add their voices to those which have already been raised.

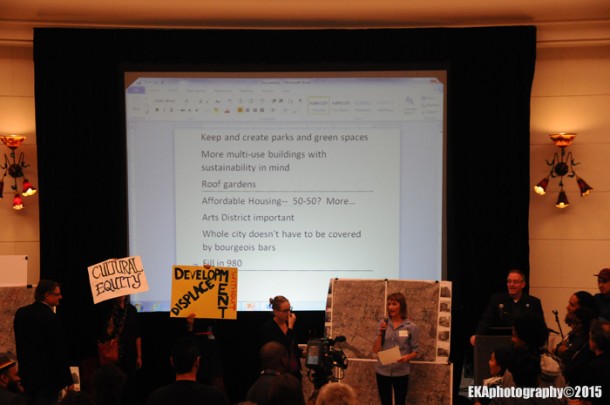

Some of the audience’s suggestions actually did get reported back

Some next steps to take would be to a) contact Gibson-McElhaney’s office or, even better for Oakland residents outside D3, your own Councilperson’s office, and let them know you support a restored Arts & Culture Commission, as well as a fully-staffed Cultural arts department; b) communicate your thoughts on what downtown’s future should be on Twitter using the hashtags #plandowtownoakland and #KeepOaklandCreative.