This is a powerful show for numerous reasons. First, the exhibit features two of the world most legendary artists. Second, the event will be held at Detroit Institute of Art, where Rivera created his masterpiece “Detroit Industry” murals. CRP has some close ties to Detroit, both because of its vast amount of public art and our connection to the legendary Techno group, Underground Resistance, who we have depicted in our mural on 28th and Telegraph in Oakland.

They’re coming back.

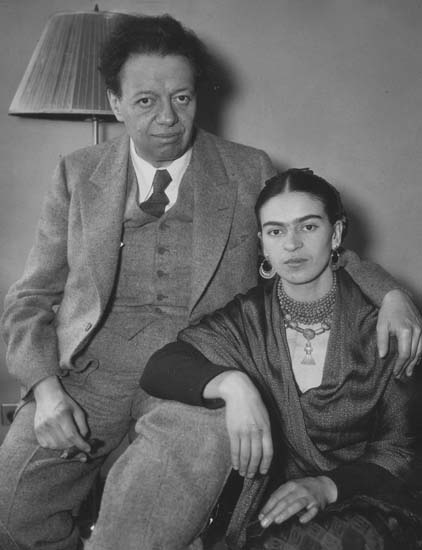

After an absence of more than 80 years, Detroit Institute of Arts officials confirm one of the world’s most famous artistic couples, Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo, will return to Detroit as subjects of a major exhibition at the museum opening in 2015.

Set in the institution that owns Rivera’s celebrated “Detroit Industry” murals and combined with work by Kahlo, whose popularity has skyrocketed in recent years, the DIA is clearly betting that the new exhibit has major blockbuster potential. A 1986 DIA retrospective on just Rivera drew 227,966 visitors over two months.

“Frida seems to pull people in wherever she goes,” said DIA director Graham Beal. “The Tate Modern in London had record crowds,” he added, when they mounted their 2005 Kahlo retrospective.

More than 350,000 people saw that blockbuster Kahlo show, said Kate Moores, a press officer at Tate Modern. She said the exhibit ranks seventh in the museum’s list of top 10 shows.

Dates have yet to be picked for “Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo in Detroit: Grand Vision and Intimate Expression,” but Mark Rosenthal, DIA adjunct curator of contemporary art, said the show will open that spring with a focus on artworks the two communists created while living in Michigan.

The pair moved from Mexico to Detroit in 1932 for a year so Rivera could work on the vast frescoes that became “Detroit Industry.” The two monumental tableaux were commissioned by Edsel Ford at the urging of the DIA director at the time, Wilhelm R. Valentiner.

By the early 1930s, Rivera was already an art-world superstar.

“There was kind of a rush to get a hold of Rivera,” Rosenthal said. In 1930, Rivera painted three murals for the city of San Francisco.

The next year, the muralist was the subject of a one-man show at New York’s Museum of Modern Art.

Indeed, when the pair arrived in Michigan, Rivera completely overshadowed his much-younger wife — a situation that’s changed significantly, in part thanks to the 2002 film “Frida.”

“The joke is that at the time of the murals, he was famous and nobody knew her,” Rosenthal said. “And now you often have to explain that Diego was the husband of Frida Kahlo.”

The 2015 exhibit, Rosenthal said, will be bracketed by a prelude illustrating what the couple created before their arrival in Detroit and a postscript that brings visitors up to date on what happened to the scandalous radicals after they left — including their divorce in the mid-1930s and remarriage to one another a year later.

‘Industry’ controversy

Exhibiting the artwork of a muralist, of course, presents problems. While impossible to bring Rivera’s other murals to the museum, Rosenthal said the DIA will display “these amazing giant cartoons he made — sketches for his murals,” which are part of the museum’s permanent collection, as well as other paintings and drawings.

The show will be installed in the museum’s special exhibition galleries, a short walk from “Detroit Industry” in Rivera Court.

Photographs, videos and newspaper accounts will flesh out the stormy relationship between the two artists.

They’ll also survey the controversy “Detroit Industry” kicked up when a range of critics, including Royal Oak’s famous radio priest Father Coughlin, attacked the murals as communistic and sacrilegious. Neither the museum nor Ford buckled under the protests, despite claims that Rivera glorified workers at the expense of management.

Something rather different happened in New York in 1934. When it was discovered Rivera painted Soviet leader Vladimir Lenin into his Rockefeller Center mural, the work was sledgehammered right off the wall.

If Rivera hogged the limelight during the couple’s time in Detroit, that year was nonetheless critically important for Kahlo, said Rosenthal, even if she despised the city she disparaged as a small town. (She disliked New York as well, and generally had little use for America.)

“This is the moment, in effect, when Frida becomes Frida,” Rosenthal said, “when she starts making the first paintings concentrating on her body,” a subject that would become her consuming focus.

The DIA owns no works by Kahlo. But Rosenthal said, “we’ll try to get virtually every object Frida made,” thought to number about 150 paintings in total, compared with Rivera’s output of thousands of pieces.

The rise of what some call “Fridamania” has much to do with the advent of feminism and Kahlo’s innate talents, said David Wistow, an interpretive planner who worked on the show, “Frida & Diego: Passion, Politics and Painting,” at Toronto’s Art Gallery of Ontario up through Jan. 20.

“Frida tackles shockingly new subjects,” Wistow said. “Not every painter would paint their own miscarriage,” a medical crisis at Henry Ford Hospital that almost killed Kahlo in 1932.

In addition, said Linda Bank Downs, author of “Diego Rivera: The Detroit Industry Murals” and DIA curator of education in the late 1980s, “Frida has the more dramatic story,” noting that she was severely crippled in 1925 in a streetcar accident that left her disabled and in chronic pain. “I think her story,” Downs said, “has really touched women in general.”

Lasting legacy

The Ontario exhibit was not the first to pair the artists. In 2011, Pallant House Gallery in Chichester, England, hosted a show devoted to the two of them.

For his part, Rivera gave the DIA a lasting legacy with “Detroit Industry” that’s made the museum a tourist destination for visitors from around the world — something that would no doubt delight curator Valentiner.

“I have the notion that Valentiner thought bringing Diego to Detroit would put the DIA on the map,” Rosenthal said.

“To some extent, you might say this was the beginning of ‘destination architecture’ — except, of course, that these are murals.”

From The Detroit News: http://www.detroitnews.com/article/20121110/ENT01/211100335#ixzz2C3OG9TOK