Retaining the character, flavor and cultural identity of Oakland should be a Big Idea. But in an urban planning process which appears to be completely run by developers and consultants, apparently with the blessing of the pro-development administration of Mayor Libby Schaff, broadly diverse voices of the artistic and creative community may have been all but shut out of that process.

As CRP previously noted, the development community has already taken aim at the arts, by filing a lawsuit this past July which claimed that the city’s percent for art program violated federal civil rights guidelines. This was followed by the Mayor’s Task Force on Affordable Artist Housing and Work Spaces, which held its first meeting August 6. In her invitation, the mayor noted that “local artist communities have contributed to making Oakland a dynamic and vibrant city that is now attracting new interest and investment. We need to ensure that they are able to remain in Oakland as the City continues to grow and change.” She went on to identify affordable housing and work spaces for artists as “part of my larger policy agenda.”

As CRP previously noted, the development community has already taken aim at the arts, by filing a lawsuit this past July which claimed that the city’s percent for art program violated federal civil rights guidelines. This was followed by the Mayor’s Task Force on Affordable Artist Housing and Work Spaces, which held its first meeting August 6. In her invitation, the mayor noted that “local artist communities have contributed to making Oakland a dynamic and vibrant city that is now attracting new interest and investment. We need to ensure that they are able to remain in Oakland as the City continues to grow and change.” She went on to identify affordable housing and work spaces for artists as “part of my larger policy agenda.”

However, a follow-up email obtained by CRP reveals that the task force invitees consisted of only a handful of actual artists and members of arts-based organizations. The overwhelming majority of those invited were developers, architects, attorneys, and city staff; some members of the arts community were added to the email chain only after they bum-rushed the original meeting without an invite. (Despite Schaff’s stated intent, the creative community has reason to be skeptical of her true motives: she is reportedly opposed to re-forming Oakland’s Cultural Arts Commission, which would bring some community oversight to the city’s overly-bureaucratic arts development process, and she reneged on a promise to arts advocates to allow for “tweaking” of the percent for art proposal to make it more community-friendly.)

Then, on September 3, a Miami-based development consultant group presented the “community kick-off event” for the Downtown Oakland Specific Plan (DOSP) – a new master urban planning initiative similar to the West Oakland and Chinatown-specific plans.

Urban planners and suits at the DOSP “community kick-off” meeting

CRP Executive Director Desi Mundo attended the meeting and posted some of his observations on social media. He noticed that very few, if any, members of the artist community were present, and said he received no answer when he inquired about community engagement specific to the Malonga Center’s tenants. The people who did attend again represented a heavy concentration of developers and city staff, along with some business owners and CBD staffers. There were several references to the creative community, but most of them amounted to lip service.

The city’s lack of a comprehensive arts master plan, non-existent Cultural Arts Council, reluctance to commission already-allocated public art funds, and current national search for a new Cultural Arts Manager, don’t add up to smart and sensible policy, much less a cohesive infrastructure, for future development of cultural corridors.

“We want these districts to maintain their unique character,” said the main consultant, adding, “What are the small things that we can do to keep the character of Oakland?” The consultant went on to note, apparently without intending irony, “there’s a lot of suspicion of growth and change.”

Much of the presentation’s focus, Mundo said, revolved around decreasing vehicle traffic downtown, and promoting walking and biking – which seemed to be a case of talking the talk but not walking the walk. As reported by the East Bay Express, two new Uptown development projects located within walking distance of BART call for the construction of more than 500 new parking spaces – which is pretty much the exact opposite of what the consultant was championing, and flies in the face of the climate action plan the city approved in 2012, which called for significant reduction of greenhouse gases in the urban center.

Similar patterns of doublespeak came from a new report on the future of Downtown Oakland by Bay Area think tank SPUR which called for expanding Jerry Brown’s controversial 10K initiative to the tune of 25,000 new downtown residents – the majority of whom would not be subject to the city’s rent control ordinance, which doesn’t cover new buildings.

Where where the artists at the DOSP meeting?

As the report’s Executive Summary stated, “Oakland’s urban center is poised to take on a more important role in the region — but the future is not guaranteed… the economy could really take off — but in a way that harms Oakland’s character, particularly its cultural dynamism, racial and ethnic diversity, political activism and identity as a welcoming community.”

If that raises a red flag, it should. An Oakland with a significantly diminished identity in the ethnic, cultural, and political sectors might as well be Emeryville, Walnut Creek or (gasp) San Francisco. The report’s title also appears misleading, since the majority of East Oakland residents are underserved by BART, making Downtown less accessible for them than other flatland residents – a point completely overlooked by SPUR. To truly make a Downtown for “everyone” would not only require more convenient and time-efficient access points than what currently exist, but might also involve expanding BART’s operating hours until at least 2am.

“Oakland’s urban center is poised to take on a more important role in the region — but the future is not guaranteed… the economy could really take off — but in a way that harms Oakland’s character, particularly its cultural dynamism, racial and ethnic diversity, political activism and identity as a welcoming community” — SPUR report, September 2015

But wait, there’s more: The report goes on to note that 80 percent of current Downtown residents are renters; Oakland’s rents have risen at the highest rates of any city nationwide; and to afford the projected average rental unit monthly rate of $3,200 by 2015, “a renter would need to earn… double the existing median income for Oakland.”

Those numbers would seem to tell the hard truth, since a $125,000 annual income is simply out of reach for many people of color, as well as the majority of Oakland’s creative community. It’s unclear, given that reality, how artists will be able to afford to live and work in an area which has received national recognition for being one of the country’s top “Art Places.”

Where does art fit into these “Big Ideas” for Oakland?

So what’s the future of arts and culture within Downtown Oakland? That’s difficult to say. The SPUR report contains several brief mentions of the Oakland Art Murmur and First Fridays – largely credited with spearheading Oakland’s cultural renaissance—but offers no concrete solutions for how to address the acceleration of gentrification, which is already threatening retail spaces as well as displacing artist spaces in the area.

Throughout the report’s 72 full-color pages, it loftily floats several “Big Ideas” and 30 smaller recommendations, only one of which is directly connected to the arts: “downtown should also integrate art into public spaces. This is an opportunity to make strategic use of Oakland’s public art fee,” the report states, even though the lawsuit could delay implementation of that fee for several years or eliminate it altogether.

The SPUR report goes on to call for more public art and large-scale installations in underutilized, walking-friendly, spaces near public transit. But it doesn’t explicitly state how an arts-based initiative might sustain multiculturalism, diversity, activism or identity – nor does it list any examples of existing public art which achieves this goal, even though there are many such examples presently in Downtown Oakland and adjacent areas. One possible point of connection is walking tours of public art installations and murals, but for this to be a solution, it would have to be community-driven, not just tourist-oriented, and conceivably linked to a proactive arts initiative with a focus encompassing more than just Downtown.

Recommending that Public Works be involved in arts planning, as SPUR does, and actually seeing that through are two entirely different things. There’s nothing to suggest PW has the capacity to take on an arts initiative, much less do so efficiently; not only has the cost of abating graffiti tags ballooned 50% over the past two years to $1.5m annually, but there are still open cases from 2012 on the books.

Overall, the SPUR report details significant potential as well as challenges ahead for Oakland, while the DOSP paints a somewhat rosier picture. Realistically speaking, the creative community’s prospects don’t inspire optimism when one connects all the dots. With development moving ahead at warp speed and rents tripling in three years, it may be too little, too late to slow gentrification. The city’s lack of a comprehensive arts master plan, non-existent Cultural Arts Council, reluctance to commission already-allocated public art funds, and current national search for a new Cultural Arts Manager, don’t add up to smart and sensible policy, much less a cohesive infrastructure, for future development of cultural corridors.

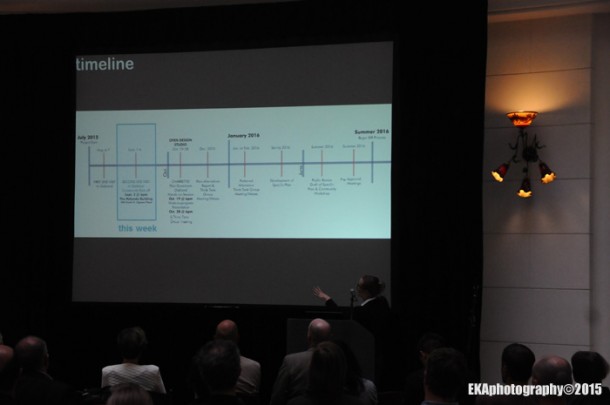

The DOSP is expected to be completed by summer 2016

Moreover, despite city staff stating their intent to do so in years past, Oakland hasn’t been able to create any notable arts districts on its own—Art Murmur and First Fridays were primarily organic happenings, and any emergence of arts districts outside Downtown have occurred despite the city, not because of it. Recommending that Public Works be involved in arts planning, as SPUR does, and actually seeing that through are two entirely different things. There’s nothing to suggest PW has the capacity to take on an arts initiative, much less do so efficiently; not only has the cost of abating graffiti tags ballooned 50% over the past two years to $1.5m annually, but there are still open cases from 2012 on the books. Furthermore, pumping public art resources into the specific locations SPUR identifies — BART plazas and the Jack London area – does nothing to alleviate the blighted parts of what SPUR refers to as the “Gold Coast” (known to the rest of us as the Lake Merritt Apartment District).

If Oakland is indeed at a crossroads, this is a critical time for advocates of arts and culture. Without significant input into the DOSP from the creative community and an arts-specific city mandate, it seems unlikely that developers, the mayor, or city staff will prioritize art that retains Oakland’s cultural identity, which appears to be already slipping away.

What you can do:

Attend the next DSOP community meeting — Oct. 20-27, 9am-6pm, 1544 Broadway.

For more information about the DOSP, click here.

One comment