It’s been said you can’t go back home again. For Community Rejuvenation Project founder and Executive Director Desi Mundo, however, that wasn’t exactly the case. After 14 years of living in Oakland, where he founded CRP — which has become the city’s most prolific producers of public murals — Mundo returned to Chicago, the city he first learned the aerosol arts in, for a two-week residency at Hyde Park Art Center, which happened to be celebrating its 75th anniversary.

In an email interview, Allison Peters Quinn, the Director of Exhibition & Residency Programs at the Hyde Park Art Center, noted that the venue has been “advancing Chicago art and artists through cutting-edge exhibitions, quality learning opportunities, creative public programming, and inventive experiences” for three-quarters of a century. In addition to exhibitions, artist talks, studio art classes, residency programs, free public events, and professional development opportunities for artists, Hyde Park’s outreach programs in historically underserved neighborhoods “bring the visual arts to Chicago youth, their teachers and their families,” Quinn said.

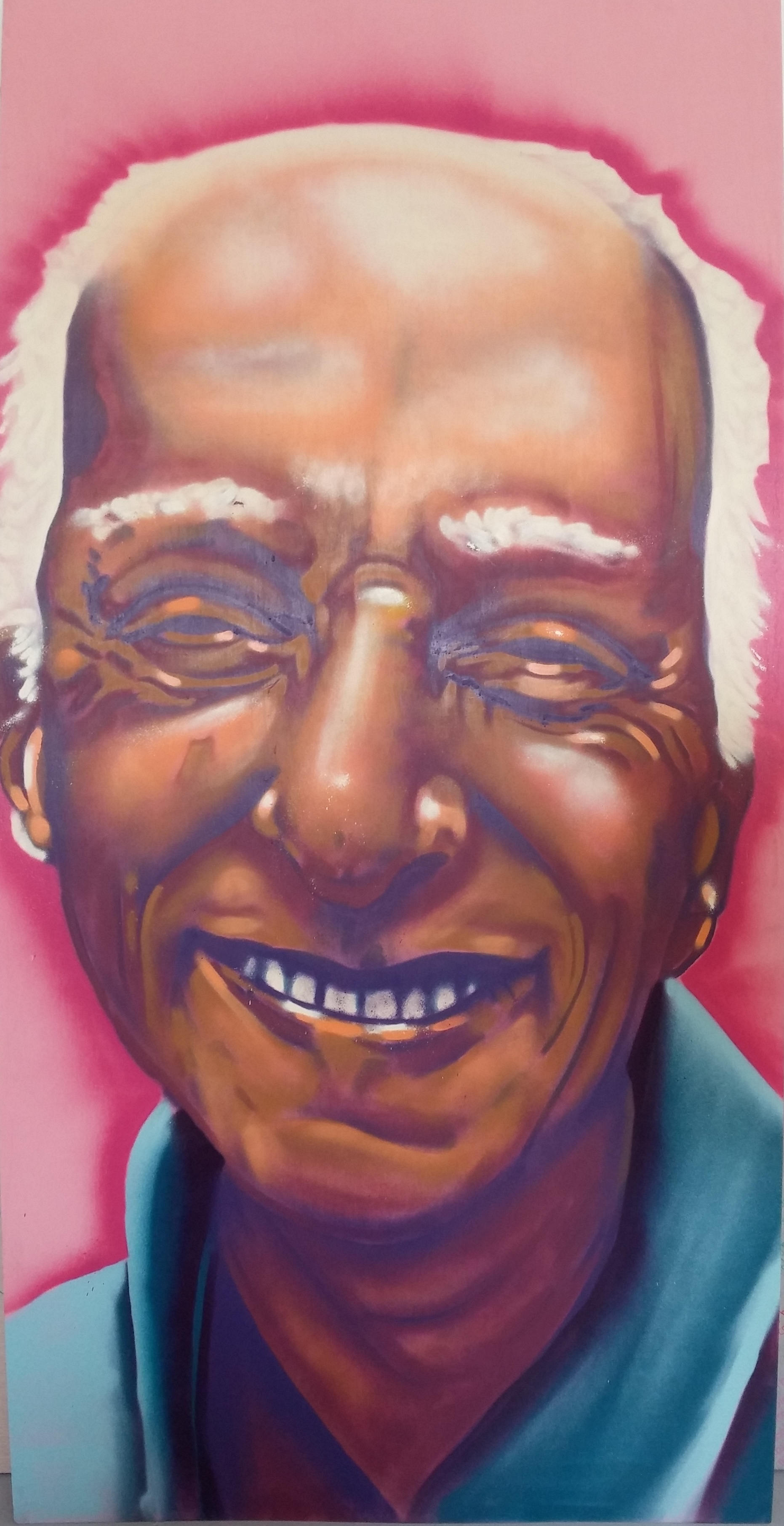

Desi paints Rubem Alves, prolific Brazilian Author and liberation theologian, live at the Hip-Hop BBQ at the Hyde Park Art Center.

Hyde Park’s gallery space, she added, “was built with public art in mind, to allow artists unique opportunities to turn the gallery inside out and include art on the street/sidewalk.”

Quinn noted that Mundo took advantage of this opportunity “by turning the sidewalk into his studio, generously allowing passers-by the chance to ask him questions and see his creative process.”

Opening up a window into the world of art and revealing the creative process of an artist at work illustrates what Quinn called the “transformative” quality of public art — “especially the process of making art and seeing art being made,” she added.

Such “transparent interaction with art and the artistic process,” she continued, inspires creative exploration and encourages exchange between audiences and artists, resulting in increased impact for both.

The completed Rubem Alves portrait.

The Hyde Park Art Center residency was produced in collaboration with Stockyard Institute and DePaul University. For the occasion, Mundo and his mentor Lavie Raven produced several portraits of liberation theologists for the DePaul Art Museum’s exhibit, “Portraits of Liberation Across Latino America.” The exhibit was curated by DePaul assistant professor of religious studies Chris Tirres, author of “The Aesthetics and Ethics of Faith: A Dialogue Between Liberationist and Pragmatic Thought.”

Desi Mundo, Virgilio Elizondo, Chris Tirres, Lavie Raven and Jim Duignan at the Portraits of Liberation Theology across Latin@ America panel discussion.

During a panel discussion panel discussion with Mundo, Raven, and artist Virgilio Elizondo, Tirres focused on social movements, art with close connections to particular communities, and the liberating potential of artforms. Noting that Mundo and Raven “choose to do their work in the idiom of graffiti art, which speaks especially to urban youth culture,” while Elizondo has “has written extensively on the significance of Mexican-American folk religion, as manifested in cultural symbols like Guadalupe or in cultural rituals like the via crucis or posadas,” Tirres said, “in each of these cases, there’s a deep respect for context and culture.”

Raven went on to describe his childhood beginning on South Side of Chicago —one of the historically underserved communities Quinn mentioned— in an Afrocentric community in 1970s, before moving to Liberia at the age of 5 and eventually Israel as a response to the repression of Cointelpro. He also spoke about being part of the modern Quilombos, Maroons, and other autonomous communities of resistance to American and Eurocentric imperialism.

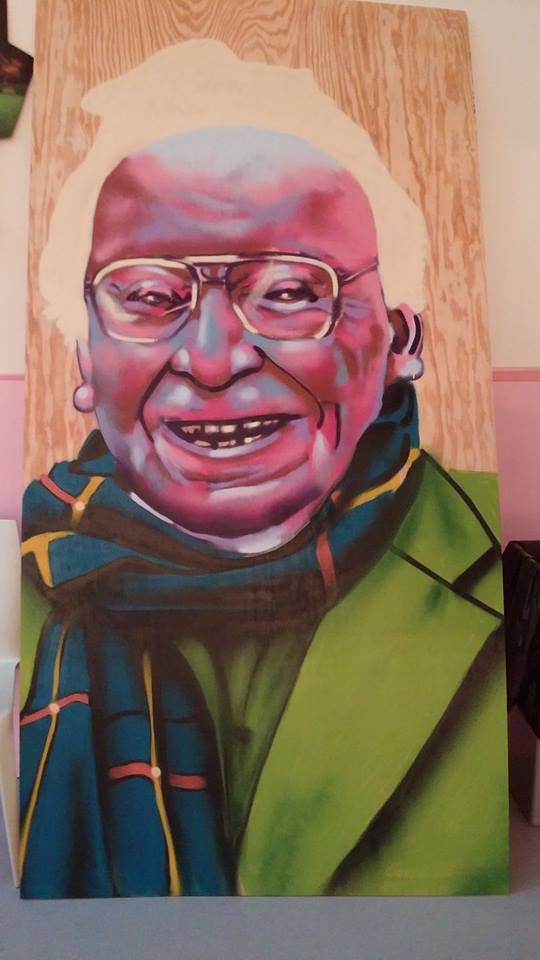

Gustavo Gutierrez who is credited as the founder of liberation theology.

Mundo traced his journey from aspiring writer to neighborhood organizer and wall curator, and his transition to cultural and political themes. He also shared that he learned from communities he painted in, such as the Lakota Sioux in South Dakota, and explained the parallels between stylistic and personal development.

The exhibition and panel discussion garnered notice from the school paper, The DePaulia, which covered the event. Reporter Nicole Cash described how Tirres’ interest in liberation theology derived from “the freedom from unjust social and political conditions in association with Catholicism” and noted how the intersection of art and education can result in a focus on social justice.

Both Raven and Mundo, the article notes, have become art educators furthering the concept of “transcommunity,” defined as “the union of divergence and different communities around a common goal.” Such a concept is important, because “we have to reflect the communities we’re working with,” Mundo is quoted as saying.

José Carlos Mariátegui La Chira was one of the most influential Peruvian journalists, as well as a political philosopher, and activist at the turn of the 20th century.

In addition to painting murals and speaking on panels, Mundo’s time in Chicago was quite eventful.

Soon after his arrival, he lectured at a Colin Ward Memorial Potluck, a community discussion series named after the late author of “The Child in the City,” a landmark 1978 book about children’s street culture. The following Saturday, Mundo participated in was hosted by Raven and the University of Hip-Hop, and featured a b-boy battle and breakbeats by DJ Rogue, as well as a celebration of “the hip-hop arts, social justice initiatives, and collective unity,” as the event description noted.

During his lecture at the Hyde Park Art Center, Mundo recounted his early influences in Hyde Park, where he grew up, before moving onto his development as an artist during his time in Oakland. Mundo focused on his evolution as an aerosol artist. “I started as a soldier in a war against the buff and the vandal squad,” he noted. “The struggle continues but the approach has evolved from a direct attack on the walls to researching the roots of the erasure system, i.e. the abatement industrial complex.”

Desi shares his experiences as an artist over the past 15 years with a packed house at the Hyde Park Art Center.

He told the story of the conceptualization and beginning of the Community Rejuvenation Project and led the listeners through its development into a pavement to policy organization. He closed the lecture with lessons learned and CRP’s current work on the Alice Street Mural Project.

He went on to note that the blight abatement industry – which has yet to actually solve “the graffiti problem” – has grown from 4 billion to 25 billion over the last 25 years, while penalties for vandals have gone from 3 days in jail to as much as 8 years for the same offense. Investment in public art, he explained, represents only 1/5th of the total economic investment in abatement, yet public art produces “far greater results,” he said.