In terms of cultural impact, Phase 2 lands as a juxtaposition of two legendary Kemetic (ancient Egyptian) luminaries: Imhotep — the architect of the step pyramid under the Pharaoh Djoser (c. 2700 BC) and a high priest of the sun deity Ra — and Tehuti (Thoth) — the ibis-headed neteru (god) of writing, magic, music,and technology. Said to be “self-created and self-produced,” Thoth maintained knowledge of the sacred words of power. Upon his journey into the afterlife, Imhotep, who was not a member of the royal family, was deified as if he were a pharaoh and later became associated with the Greek god of medicine.

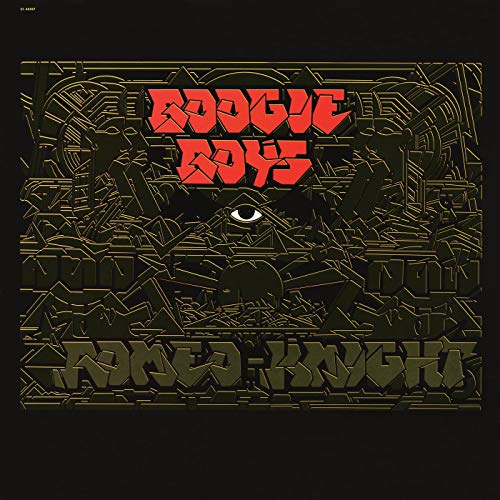

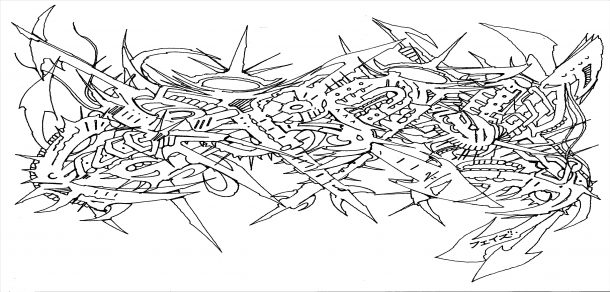

The analogy may seem like a reach, but not when you consider that Phase embodied hip-hop mythology at its most potent, even mystical. One of hip-hop’s most creative visual artists and true visionaries, he had no formal artistic training. A guardian of the notion of hip-hop purity, his letterforms became the basis for innumerable expressions by future writers, extending into the realm of typography in general. And he was known to gift writers with outlines — the hip-hop equivalent of a sacred papyrus scroll. He even incorporated Kemetic imagery, such as pyramids and the Eye of Horus, into his art.

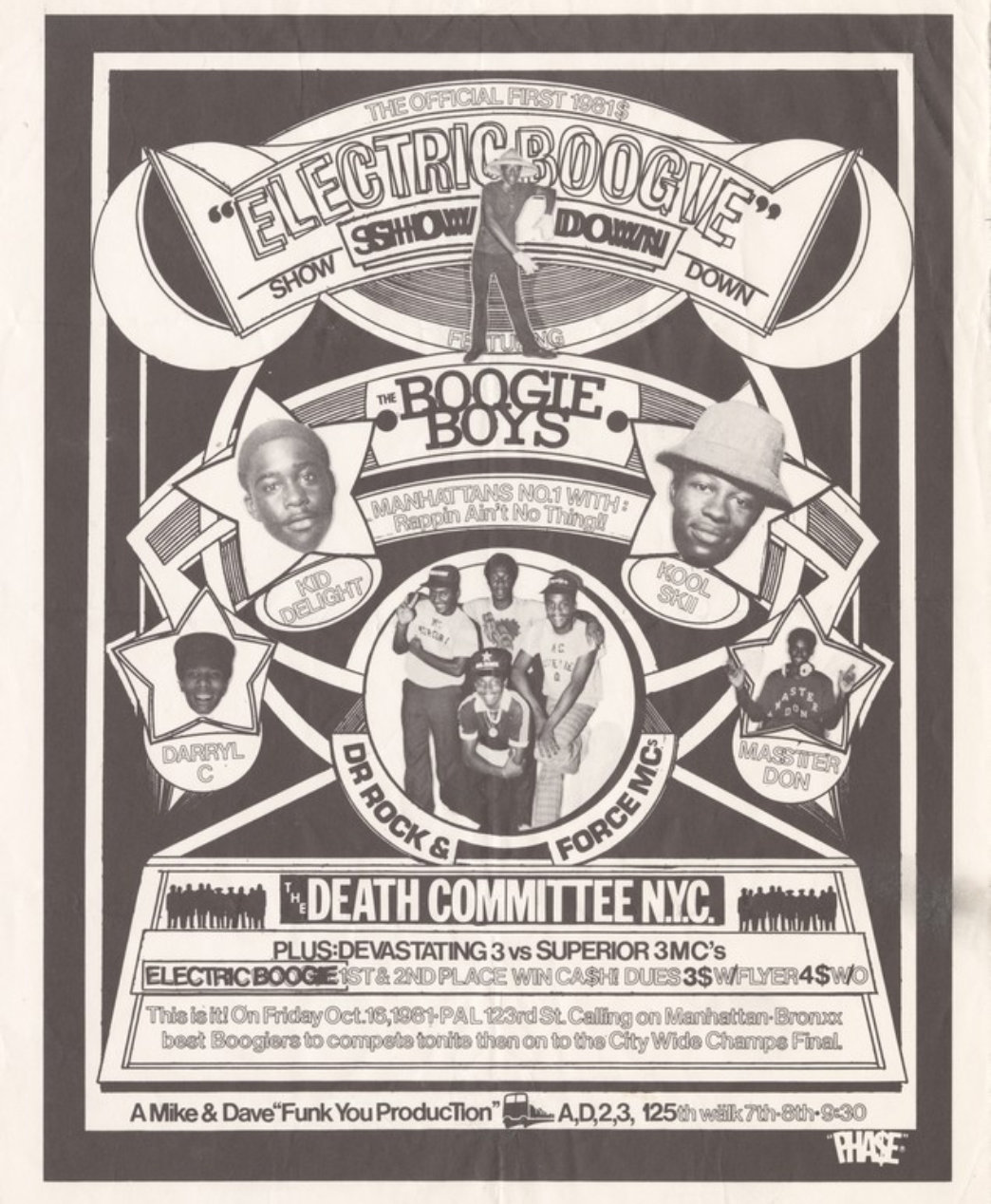

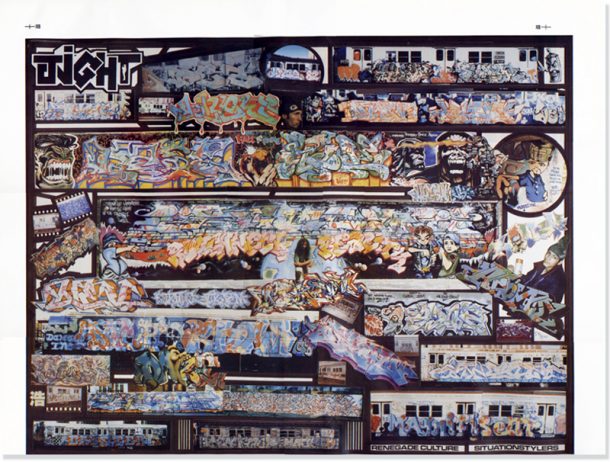

Born in Manhattan but raised in the Bronx, Phase predates hip-hop’s most commonly-accepted origin narrative: By 1971, he was constructing and deconstructing letters on subway train canvasses, and in 1972, he was part of the first aerosol art gallery show, as a member of United Graffiti Artists (UGA). He became one of the original b-boys when DJ Kool Herc’s parties jumped off in 1973, and in addition to being a prolific aerosol artist in the streets of NYC, he created a slew of classic hip-hop flyers for Grandmaster Flash and many others during the classic old school era, was proficient as a DJ and beatmaker, and even recorded two 12” singles as an emcee in the 80s.

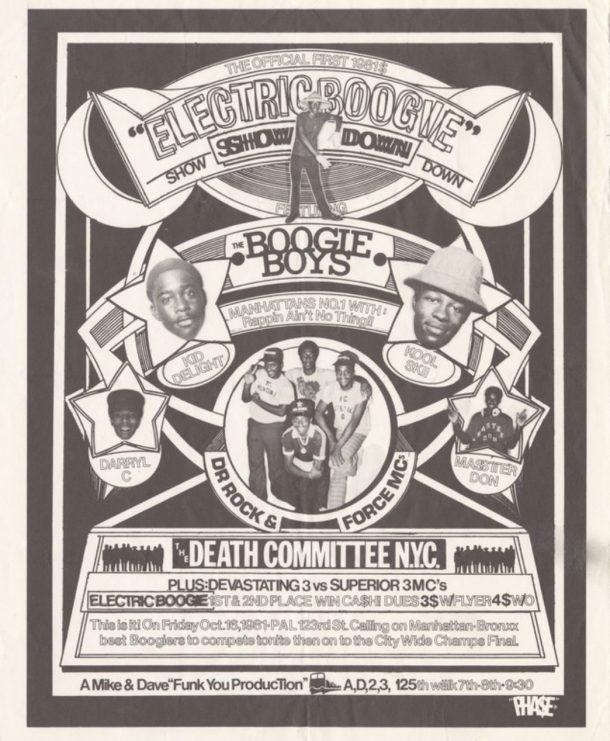

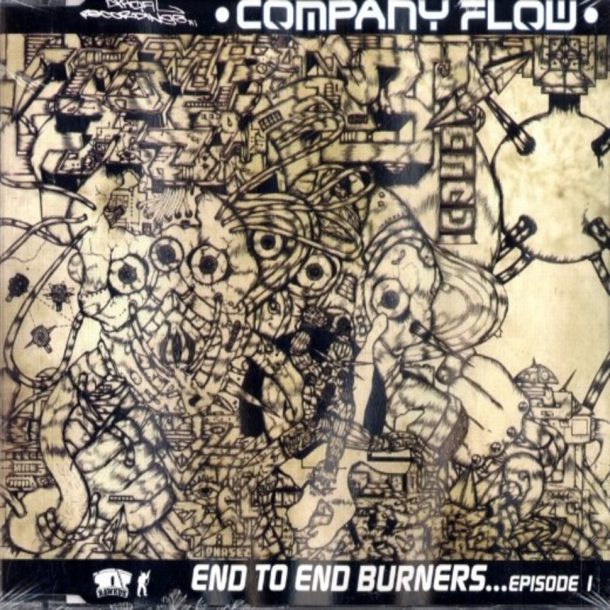

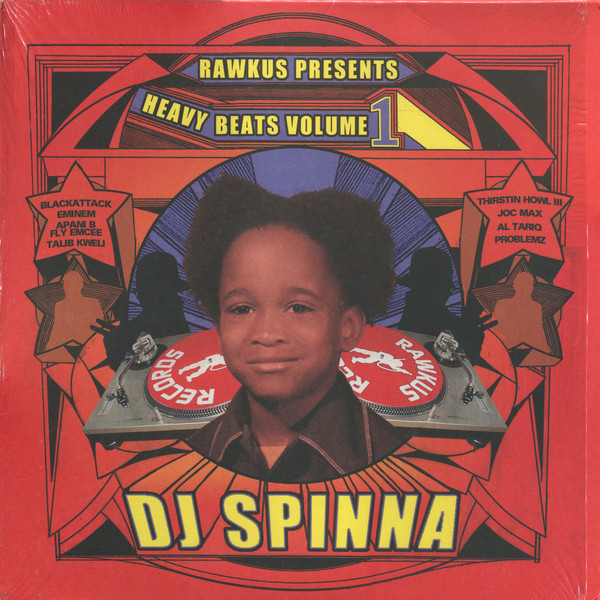

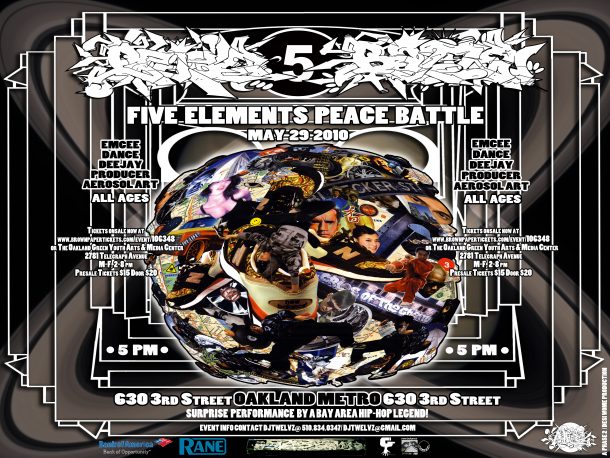

Known as the inventor of the softie or bubble letter style, Phase went on to blaze trails in graphic design, creating logos and album covers for the Crash Crew, Tuff City records, the Boogie Boys, Company Flow, and DJ Spinna — paving the way for later writers-cum-designers like Futura 2000, PNB, Haze, Doze Green, Gemini 7, and Shepard Fairey (and the list goes on).

“He was willing to share information and pass things on and that was, for him, that was part of fighting to maintain the integrity of the culture.”

In the 1980s, as the art director for the zine International Graffiti Times (whose name was later changed to International Get-Hip Times), he advocated for the authenticity and integrity of the underground subculture in the face of widespread commercialization and co-option. As he told the Eye on Design blog, “Basically (with IGT), we were dropping kamikaze news and mind states that were meant for whoever was hip to reality. No holds barred and not for the marshmallow-in-denial types. It was the source before The Source.”

A creative dynamo, Phase continued to develop new artistic letterforms and stylistic techniques well into the 2000s and beyond. Both a direct and indirect influence on five decades of the evolution of the hip-hop aesthetic, he didn’t always suffer fools gladly. He could be notoriously brusque to those who offended his cultural sensibilities — somewhere along the line, he decided to eschew “the G word” (graffiti), which he considered demeaning, and co-optive — yet he was also known for being a mentor to writers he barely knew and/or had never met personally.

Phase’s passing on December 12, at the age of 64, isn’t just the end of an era; it’s the end of the multiple eras (and, possibly, the beginning of a new phase). As news broke, the inevitable tributes from the writer and core hip-hop communities rolled out on Instagram and Facebook, along with equally-inevitable eulogies/tributes in such publications as ArtForum and the New York Times.

As ArtForum noted, “As a graphic artist, he lent his hard-edge geometric style—influenced by the Bronx’s many Art Deco theaters—to flyers promoting significant parties and shows like 1982’s Kool Lady Blue at the Roxy nightclub in Chelsea, which established a rapport between hip-hop and New York’s contemporaneous punk and New Wave scenes.”

The NYT bestowed similarly-magnanimous props: “In the South Bronx at the dawn of the 1970s, all the creative components that would coalesce into what became widely known as hip-hop were beginning to take shape. At the center of them all was Phase, an intuitive, disruptive talent who first made his mark as a writer of graffiti — although he hated the term. …His influence on the burgeoning art form was seismic.”

Though effusive in their praise of Phase’s cultural and artistic contributions to hip-hop and the urban visual landscape, many of these elegies seemed truncated and less-than-comprehensive; to properly detail Phase’s life and career would require a full-on documentary and/or biography.

“We were dropping kamikaze news and mind states that were meant for whoever was hip to reality. No holds barred.” – Phase 2

It’s crazy to think that a figure who was active in so many evolutionary stages and facets of hip-hop and influential on so many levels, wasn’t considered a founding father of the culture by the mainstream media — until perhaps now, after his transition. The so-called “Holy Trinity” of hip-hop — Herc, Flash, Bambaataa — makes for good copy, but anyone who was there (or dug deeper than Jeff Chang’s “Can’t Stop, Won’t Stop”) knows that storyline is incomplete and historically problematic. Not only did Phase connect the dots between the early aerosol movement and the bedrock foundations of hip-hop — in addition to being present at Herc’s earliest jams, he’s credited with being a founder of the New York City Breakers and the inspiration for Phade in “Wild Style”– he was a pioneer of street promotion and an innovator of hip-hop’s stylistic aesthetic, at a time when the now-global culture was fledgling and uncertain of its future. The term “Renaissance Man” rarely applies to modern individuals, but in Phase 2’s case, it’s spot-on.

As we reminisce on this legend, it would be remiss not to point out Phase’s connection and influence on CRP, as a mentor and sometime collaborator of ED/founder Desi Mundo. Mundo was mentored by some of Chicago’s veteran writers, yet he considers Phase and his protege Vulcan influences which helped him challenge him to push past his own artistic limitations.

Mundo recalls becoming personally acquainted with Phase2 during the MySpace era. “I saw he was on there and i added him. I didn’t know if it was the real (Phase 2) or not. And the next thing you know, I got a message in my inbox.

“One of the main things he kind of insisted from the gate was to not refer to things by the G-word. He was telling me history and just talking to me about philosophy. Because he was a practitioner of all of the culture he was hip to some of the dancers that were in my crew, and was familiar with the entire scene. It was kind of like (Marvel Comics’) The Watcher. He was aware of all these different facets of hip-hop culture.”

Many hip-hop practitioners focus on one element, Mundo says. “They have cursory knowledge. But (Phase) was an active participant in everything.”

For a younger writer like Mundo, interacting with Phase was like witnessing history come to life. “He had participated in generations that I had read about, written about, and studied on my own. He was giving you that first-hand information. Its part of that engagement and historical research process of CRP, we really want to engage history in our work.

Over time, the two would have long conversations and collaborate on graphic design projects. Phase would share knowledge of the culture, a master’s understanding of artistic techniques, and his own homemade beats.

Eventually, he sent Mundo an outline which was projected onto a wall and incorporated into the design of the “Peace and Dignity” mural — a project Vulcan also contributed to. “He ended up providing us with letters we projected onto that wall.”

Most of their exchanges were long-distance, Mundo says. “But I did meet him in person when I went to New York.

“What’s crazy is, if you look at the tributes, there’s a lot of people who are telling these real personal stories about him. I’m definitely not unique. He did this with everybody for generations. He was willing to share information and pass things on and that was, for him, that was part of fighting to maintain the integrity of the culture in the face of gentrification. He was a purist.

“He wasn’t like one of these old-school writers who never mastered technology or evolved their style. Phase’s style always evolved. It was by far the most futuristic style of writing that there is.”

Summing up Phase’s significance to hip-hop, Mundo says, “If you really look at the history, he was writing before Kool Herc threw that party at Sedgwick, I think he was at that party. And Kool Herc was in his crew as a writer. You’ll see Herc’s tags on some of those original flyers. … I almost think he was present in every moment of hip-hop history.” Which brings us full circle to the analogy with Thoth, whose attributes included being omnipresent and omniscient.

Peace out, Phase 2, and thanks for everything.