Oakland’s Cultural Affairs Department (CAD) is severely underfunded and understaffed. According to a memo sent by CAD to the Funding Advisory Committee last November 26, current staffing levels are just one full-time employee and one temporary service contract employee. $1.2 million in grants were awarded in the last fiscal year, a number which has not seen a significant increase since before the recession. (By way of comparison, the San Francisco Art Commission handed out $1.6 million in grants in 2014-2015 –the most current numbers from its Annual Reports — while the City’s Grants for the Arts program totaled $9.5 million in 2017-2018 — an increase of more than $350,000 from 2014-2015.)

This is a travesty in a city which is literally bursting at the seams with artistic talent and cultural flavor. The boom in development — the Uptown neighborhood alone has seen in excess of $1 billion in development projects since the Brown administration — has clearly not trickled down to artists; in a 2015 survey conducted by the City, almost half of the 900 artists who responded reported they had been displaced or were at risk of displacement.

Among those displaced artists is two-time Grammy winner Fantastic Negrito, whose Blackball Universe HQ was pushed out of Jack London Square and into West Oakland. Art spaces are also at risk: longtime Art Murmur mainstay the Vessel Gallery has taken up a nomadic existence at The Alice Collective after being displaced from Uptown, and the management of black box theater space the Flight Deck recently announced it would be closing in 2020 — displacing all of its resident companies and creating a void in small theater spaces Downtown. The aftermath of the Ghost Ship fire in 2016 directly led to dozens of evictions of DIY artist spaces. Even murals have suffered displacement, including two of CRP’s most-celebrated works, “Peace and Dignity” and “The Universal Language” — the latter literally obscured by a multi-story development.

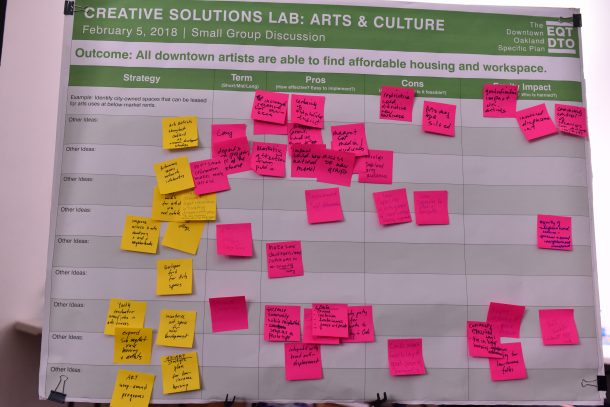

“Sticky notes on a whiteboard and well-intentioned, yet aspirational, policy documents are not the same as actual, tangible, and concrete solutions to the challenges facing Oakland’s cultural sector”

The City has ostensibly made efforts to identify solutions: A Task Force convened by the Mayor issued a series of recommendations for cultural protection in 2016; in 2017-2018, local arts and culture practitioners were engaged as part of its outreach for the Downtown Specific Plan in 2017 and 2018. And in 2018, the Cultural Plan–and its guiding principle of Cultural Equity–were announced with great fanfare. But sticky notes on a whiteboard and well-intentioned, yet aspirational, policy documents are not the same as actual, tangible, and concrete solutions to the challenges facing Oakland’s cultural sector.

Meanwhile, in the past few years the number of applications for the Cultural Funding Program (CFP) has trended sharply upwards. The deluge of applications has meant that many deserving applicants go unfunded and/or grant awards have been reduced in order to fund more projects. At the same time, according to the CAD memo, the department’s “current workload… exceeds staffing capacity.” There is a backlog due to lack of staffing resulting in delays in check disbursements of 4-5 months, compounded by a 23% increase in overall grant applications. These delays sometimes influence project timelines, requiring artists to develop workarounds.

The lack of funding has had other impacts, too. In the 2018 Cultural Plan, a cultural asset map was commissioned which was not as comprehensive as it could have been, because there weren’t enough funds to correctly apply this task. As a result, critical data remained uncollected, which makes it more difficult to evaluate the extent of Oakland’s cultural sector. Even so, the data collected did show that Oakland’s cultural economy generated in excess of $390 million overall in 2017 — yet that figure, which includes cash cows like music- and film-related businesses as well as the Oakland Museum (whose annual budget exceeds $10 million), are somewhat deceptive: almost 60% of Oakland’s arts-based non-profits have operating budgets of less than $250,000 annually and many of those are under $100,000.

While the Downtown Specific Plan draft calls for the involvement of Cultural Affairs in many of its strategies and recommendations, implementing these plans would require increased bandwidth the department simply doesn’t have at this point. Without more money to hire staff and/or consultants, it’s unclear where this bandwidth would come from. This situation threatens the City’s ability to realistically deliver the equity called for in its Cultural Plan.

“Almost 60% of Oakland’s arts-based non-profits have operating budgets of less than $250,000 annually and many of those are under $100,000”

Furthermore, attempts at increasing cultural funding and staffing have fallen on deaf ears at City Hall. A modest bump in funding in the FY 17-19 budget was not renewed in the current budget. The budget did include a one-time appropriation for City-funded murals, but only half of the requested $200,000 was secured. $100,000 might sound like a lot for public art, but not when you consider that amount is split between eight Council districts. $12,500 per District is hardly enough for a large-scale mural–which can easily run upwards of $50,000–meaning that artists will most likely have to cobble together additional funding to complete these projects, or simply not attempt large-scale projects to begin with.

In an attempt to be proactive, Oakland’s Funding Advisory Committee (FAC) recently shifted some aspects of the Cultural Funding Program. The Art in the Schools (AIS) category was “temporarily” suspended, with its appropriation going to the Organizational Project (OP) category. And the grant amounts for Individual Artist Project were raised slightly, to a maximum of $7000 — the first increase in this category in 25 years.

Shifting the AIS funding to OP makes sense from a capacity standpoint, as it means less paperwork for Cultural Affairs staff and a streamlining of process. But it could also result in fewer overall applications for educational projects, or less overall funding for arts organizations due to restrictions on the number of applications for any one category.

Arts advocates have little choice but to continue to call for an increased arts budget and hope someone at City Hall hears; despite significant risk of artist and art space displacement, supporting the cultural arts has clearly not been a top priority of the City. As a result, Oakland’s cultural diversity, as well as its cultural identity, are being eroded as you read this.

If ever a time called for creative solutions, this is it. There are a few scenarios which could reasonably play out, in order for artists to be able to continue to live and produce art in Oakland,

- Secure more outside funding from the private sector.

- Seek non-traditional funding models.

- Reallocate the Transit Occupancy Tax (TOT).

In Scenario one, artists could work with an art broker who negotiates commissions directly. This model is already in existence, but its downside tends to be an overall lessening of community engagement and/or political and social expression. There is also the option of artists directly interacting with corporate sources, including the development community, but this path may require a skillset which some arts organizations don’t have. Projects which align with both corporate social responsibility and arts organizations’ values, however, would have a huge upside; the downside is this creates a system of patronage which may not be egalitarian.

Scenario two could take on many forms. One recent example could be the Museum of Graffiti in Miami’s Wynwood district, a project curated by Alan Ket, whose permanent collection includes works by legendary writers such as Dondi, Phase 2, Rammellzee, and Doze Green. The Bay Area aerosol scene boasts a long history dating back to the mid-80s, and has produced many celebrated artists, from Dream TDK to Barry (Twist) McGee, but lacks any kind of permanent collection or institutional home. Occasionally, museum spaces like OMCA and YBCA have commissioned pieces or exhibited aerosol artists, but these have all been temporary.

“Oakland’s cultural diversity, as well as its cultural identity, is being eroded as you read this”

Another strategy might be collaborative projects between arts organizations and non-profits in fields not commonly associated with art, such as mental health, environmental justice or public safety. These collaborations aren’t uncommon — CRP has collaborated with numerous organizations in the past — but may need to be intentionally prioritized as a matter of sustainability, if artists are to remain resilient in a gentrified “New Oakland.”

A combination of the first two scenarios is also possible. For instance let’s say an arts organization is able to secure money from a developer for a mural project as part of a community benefit agreement. Then, the arts organization partners with a non-profit to add additional bells and whistles–such as increased community engagement and outreach–for which it is able to pursue additional grants. In this scenario, the initial funding becomes seed money to attract additional investment, resulting in a multi-faceted project with numerous components. Making this scenario work requires alignment between the arts organization and the non-profit in terms of mission and values, but it is a feasible, although complicated, possibility, which requires coordination and communication skills.

The third scenario requires the most heavy lifting but also would result in a best-case outcome. Oakland’s TOT revenues are divided between institutions like the Zoo, Oakland Museum, and the Cultural Affairs Department, and Visit Oakland — which receives the lion’s share of this fund to promote tourism. Reallocating the TOT to increase arts funding is mentioned as a strategy in the Downtown Plan, but it’s not something the City Council can simply amend on its own. It would require a ballot amendment and a 2/3rds majority vote by the electorate. Which means not only would arts advocates have to write up policy language, but collect enough signatures to place the amendment on the ballot, and launch a public awareness campaign (which could face well-funded opposition from the hotel industry).

Yet while the hotels might cry wolf, the fact is more of them are coming online in Oakland. So even if Visit Oakland’s percentage of TOT was adjusted, its funding stream will continue to rise over time, while Cultural Affairs might receive enough funding to return to sufficient staffing levels, restore its AIS program, fund more artists, and collect the amount of data required to comprehensively evaluate Oakland’s cultural economy.