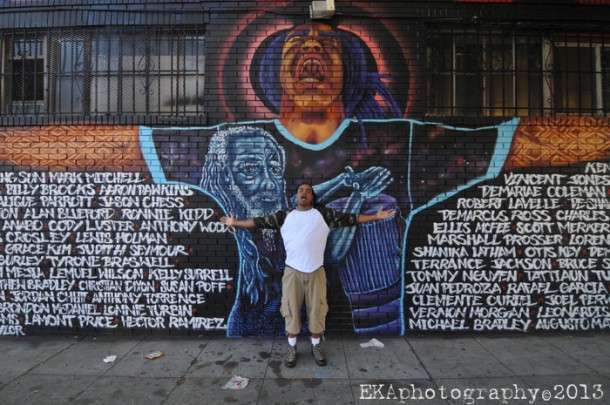

Graffiti is a polarizing word. Rampant tagging in urban areas contributes to blight, which according to law enforcement experts, decreases property values, and invites further vandalism and illegal dumping. These urban hieroglyphs are frequently a hot-button issue for both the media and elected officials; their sensationalistic rhetoric has turned the abatement industry into a $20 billion behemoth. For that reason, many practitioners of the form prefer the term “aerosol artist” – noting that the punitive measures often prescribed tend to criminalize the aesthetic, even on legally-sanctioned works.

This mural, partially funded by the city’s abatement mural program, has remained tag-free.

In late 2012, Oakland decided to address its tagging problem, which had reached epidemic proportions, with an an anti-graffiti ordinance. This ended up being a spectacularly bad piece of policy, in that it didn’t do what it promised to do – it was basically unenforceable (since OPD doesn’t investigate graffiti), which meant that no civil cases were brought, no fines were assessed, and no Victim’s Compensation Fund ever materialized. The ordinance did succeed in increasing existing fines for property owners, however.

Murals in Chinatown have beautified the neighborhood and substantially reduced tagging.

The ordinance’s one silver lining was the appropriation of $400,000 in the ’13- ’15 budget for an Anti-Graffiti Mural and Green Wall program—which came about because the Community Rejuvenation Project (CRP) and other arts organizations advocated for the benefits of murals at public meetings. Yet that program has been problematic, as well. City Councilmembers and the Cultural Arts Department argued over who was going to administer the program, which led to no projects being commissioned for more than a year.

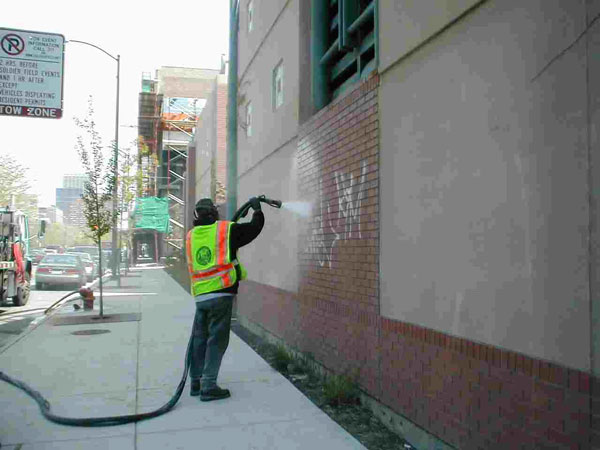

Graffiti abatement firms are notorious for overbilling clients.

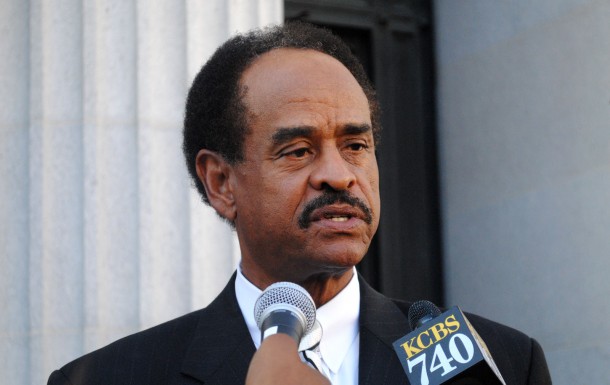

City resolution 15-1272, passed on July 19, 2016, appears to be an old-fashioned money grab: it stipulates no recipients, other than Larry Reid, and an extremely-vague set of lofty-sounding deliverables.

Once that was settled, Councilmembers were slow to commission projects and allocate funds. And there was no official citywide announcement identifying the program, so artists who could have been funded by it may not have known of its existence. There was also no standard protocol between Councilmembers regarding the program.

Meanwhile, abatement costs for graffiti removal on public property were creeping up—surging to $2 million in 2014, double what the city was paying at the time the anti-graffiti ordinance was enacted. The high cost and lack of effectiveness of abatement was actually one of the stated reasons why the mural fund was created.

A “before” shot of the Alice St. mural shows how rampant vandalism was.

CRP was curious about where the money for this program had gone, so we made a Public Records Request. Specifically, the request asked for all public records related to the allocated $400,000 and how they were used.

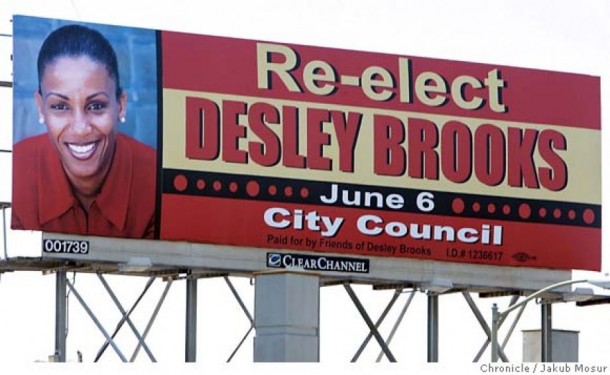

What we found was interesting. CM Kalb’s office–the only District to publicly announce the fund–was easily the most responsive to our request, posting eight separate files of documents. CM Kaplan also posted a record of her District’s approved project. But CM Brooks’ office claimed to have “no responsive records,” while CM Guillen’s office claimed they needed more time to compile records, which they promised to do by December 20 of last year (we’re still waiting). No other Councilmembers responded.

CM Brooks’ office falsely claimed there were “no responsive records” to records to CRP’s Public Records request.

So we kept digging. What we found was even more interesting.

Additional records were obtained by searching the city of Oakland’s website database; there are also records located on the Public Art Advisory Committee page.

The grants range from modest ($600 for a mosaic trash can), to mid-size ($5000 for two murals in the Fruitvale; $7000 for a mural at East Bay Asian Youth Center), to sizeable ($42,500 for Attitudinal Healing Connection “Oakland Superheroes” murals; $38,000 for a series of murals coordinated through Eastside Arts Alliance.) Most of the grants and amounts seemed reasonable, depending on the scale of the project. (Full disclosure: CRP received $4,500 for two separate mural projects.)

Detail from AHC’s “Oakland Superheroes” series, which received Abatement Mural funds.

We did find a responsive record for Brooks; she signed off on utility boxes in District 6, to be commissioned by non-profit group OCCUR, allocating her District’s entire share of $50,000 to one project.

When we examined CM Reid of District 7, however, something smelled funky. Reid issued $25,000 of his fund to the East Oakland Beautification Council (EOBC), who do graffiti clean-up, but aren’t mural artists themselves. The Council resolution, passed in July of 2016, misstates the original purpose of the fund, which was advocated for on the explicit basis that simple abatement is ineffective and cost-inefficient. Although the fund is named “Graffiti Abatement Mural and Green Wall,” there’s no mention of either in the EOBC’s deliverables.

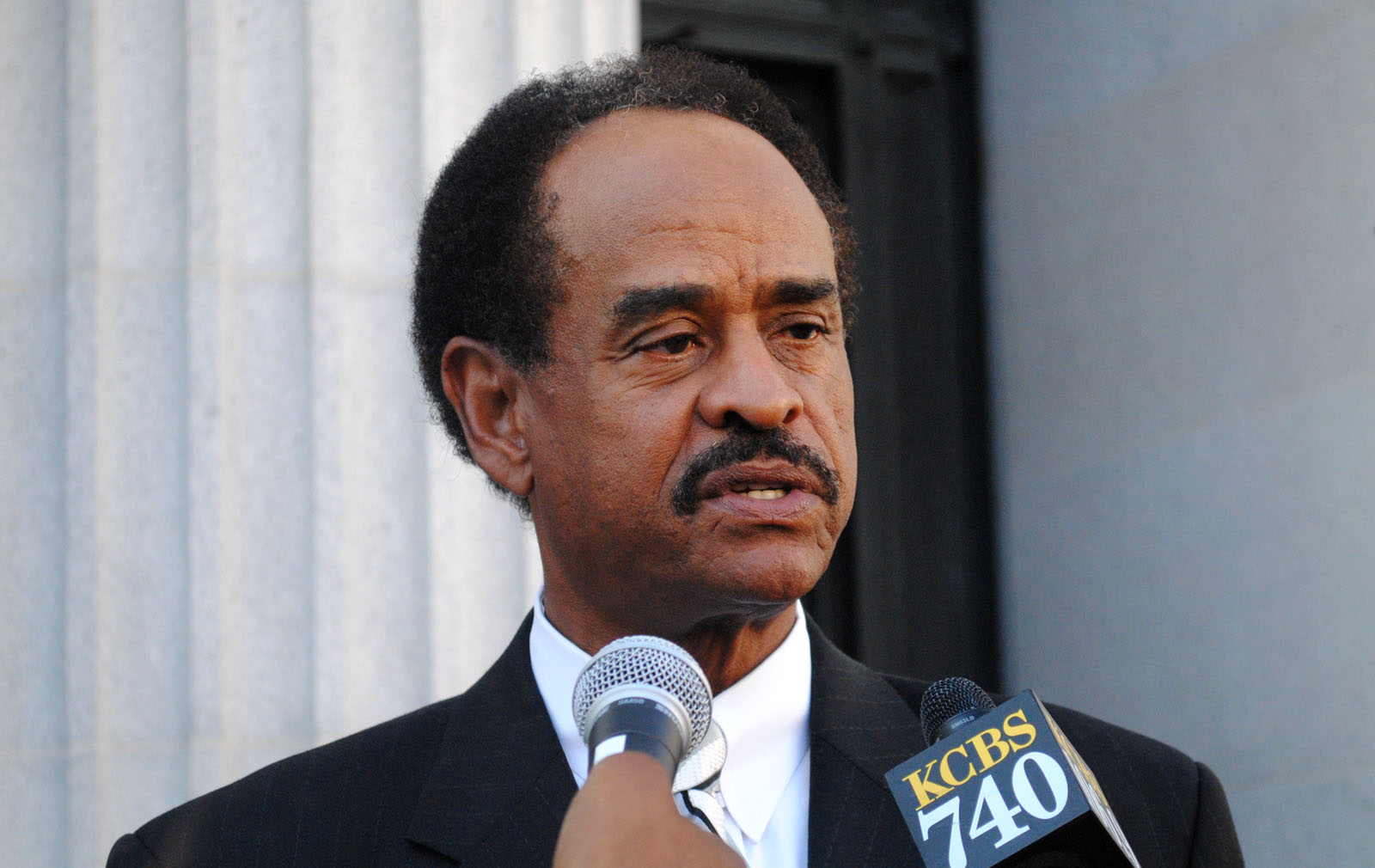

CM Reid allocated $50,000 earmarked for Abatement Murals to questionable non-mural projects.

Why would the city need to fund private abatement efforts, if the anti-graffiti ordinance is effective? And if the ordinance is ineffective, why should the city pay more for abatement than the $2 million it already spends?

Instead, the resolution notes the $25k is “to eradicate graffiti blight and to beautify the culturally rich District.” There’s a slight reference to the EOBC providing documentation, but it’s unclear if this is a new project or for EOBC’s past efforts. The resolution provides no specific details about the project area or a deadline for submitting documented results. The resolution states the money is to be used for “additional effective abatement and deterrent methods,” which sort of assumes the unspecified methodologies employed will automatically be successful. No additional details are provided in the Council’s Agenda, and since there was no mural attached to it, the EOBC’s grant was also not subject to PAAC review–unlike many other commissions funded by the same program..

The EOBC grant appears to be a large chunk of money with very few strings attached, directed toward the opposite purpose. Which might technically be illegal, and may violate ethics standards as well.

The EOBC’s “Graffiti Cove” appears to violate DoJ gudelines against “glorifying graffitti.”

But that’s not the only possible misuse of funds by Reid, the current Council President. A week prior to bequeathing $25,000 to EOBC, Reid gave the other half of his District’s funds to himself.

City resolution 15-1272, passed on July 19, 2016, appears to be an old-fashioned money grab: it stipulates no recipients, other than Reid, and an extremely-vague set of lofty-sounding yet unspecific deliverables. As stated, “it is likely that an innovative public/private partnership approach, which supplements blight abatement services, could make a significant, positive improvements to the community’s overall livability, appearance, and social and economic stability.”

Despite the EOBC’s claims of eliminating graffiti along the San Leandro corridor, this picture tells a different story.

As it goes on, the resolution gets more and more pretentious and pontificate in its language: “each Council District has the ability to analyze its local problem in order to ascertain certain conditions and select the appropriate response in addressing illegal graffiti,” it says, without ever clearly stating those conditions.

The next part is even more puzzling: “Whereas, measuring the effectiveness of Oakland’s present illegal graffiti abatement initiatives is needed to determine whether these methods have succeeded based on the U.S. Department of Justice Graffiti Guide.”

Blanche Richardson’s Marcus Bookstore was threatened with a $2,000 fine from the City of Oakland until CRP protected this local treasure by painting a free mural for them.

What’s confusing about this statement is that it came three years after the anti-graffiti ordinance was passed–presumably, Reid is aware of the ordinance’s overall ineffectiveness, and that abatement costs have spiraled, just as CRP predicted in 2012.

Furthermore, the resolution never establishes that Reid’s office (or a proxy) will actually conduct a study or collect data to determine measured outcomes of “abatement initiatives.”

This memorial mural helped to cool down a violence hotspot in D6.

Next, the resolution again references the Department of Justice’s Graffiti Guide, which purports that reduction or elimination of graffiti can be achieved through tracking quantifiable factors (i.e., amount, size, number, type, location and “length of time graffiti-prone surfaces stay clean”).

It’s interesting, to say the least, to see the DoJ guidelines quoted so heavily, since the EOBC’s “Graffiti Cove” project appears to violate some of those guidelines. Reid’s resolutions also conveniently omit DoJ findings that “murals… may reduce incentives to vandalism.”

According to federal guidelines, murals can substantially reduce vandalism.

At no point does the resolution establish that tracking of outcomes will be conducted. Neither does it define any methodology (such as data collection or the issuance of a comprehensive study) to be used, nor any sort of timeline for producing results.

CRP murals on the Richmond Greenway have enhanced the city’s cultural richness and kept blight at bay.

The kicker, though, is this section: “in most cases an effective strategy will involve implementing, in addition to green walls and murals, several different responses to illegal graffiti.”

Here Reid justifies his usurping of the community advocates’ intent, by boldly proclaiming his right to bypass that intent. What’s also problematic, as CRP pointed out in 2013, is the abatement industry is notorious for overbilling and in some cases fabricating illegal graffiti, and has not proven sustainable over time, as evidenced by rising costs for both public and private abatement services.

Ken Houston of the EOBC, which received $25,000 for a project with vaguely-worded deliverables.

Reid then doubled down on his rhetoric, claiming “direct action is required with a comprehensive solution, to ensure long-term sustainability of urban vitality.” This action isn’t ever explicitly stated, though, other than the broadly-worded “additional effective abatement and deterrence response methods.”

It’s also unclear what the “comprehensive solution” he’s referring to is, since there’s no specific data collection or methodology attached to the resolution.

Caroline Stern’s Little Stars was mural, funded by Oakland’s Abatement Mural program.

However, any truly comprehensive study would not only include cost-benefit assessments of basic abatement, but cross-reference those findings with assessments of alternative abatement strategies, including murals. Without these components, it’s difficult to imagine outcomes which aren’t predictable and/or already outlined in federal guidelines. A study which directly compared the effectiveness of basic abatement vs. alternative methods could actually result in sustainable solutions–and cost-reduction for city budgets.

Would a comprehensive study confirm the cost-effectiveness of murals, as opposed to buffing walls?

In the absence of a comprehensive study, we are left with Reid’s two resolutions, which throw more money into the abatement black hole, yet are lacking in substance.

Do these slickly-worded resolutions constitute ethical violations by the Council President?

Another question: what do we have to show for the $50,000 Reid gave to himself and the EOBC?

The City of Oakland spends more than $2,000,000 annually on ineffective graffiti abatement.

Even more questions remain: why would the city need to fund private abatement efforts, if the anti-graffiti ordinance is effective? And if the ordinance is ineffective, why should the city pay more for abatement than the $2 million it already spends–more than twice the amount of the entire Cultural Arts Fund budget–? Wouldn’t it make more sense to prioritize alternative abatement solutions, given that at best, basic abatement is a costly and temporary solution?

All we know for certain is that many areas of Oakland have a serious tagging problem, not just District 7—which undercuts the argument that Reid’s District is somehow uniquely impacted by vandals and therefore justified in dipping into a mural fund for unspecified abatement activities.

It’s telling that, out of eight Council Districts, every single Councilmember allocated their portion of the $400,000 community advocates won for alternative abatement methods towards mural projects—except one: Larry Reid.

One comment