Restorative Justice for Oakland Youth founder, Fania Davis, is honored on 5th St near Market. This location, previously a hotspot for vandalism, has remained untouched since CRP placed a mural honoring local heroes there.

In a recent Oakland Tribune article —provocatively titled “Extortion or Art”– reporter Matthew Artz put forth that “the city is enjoying a golden age of murals and street art. But it also is grappling with a graffiti epidemic like none it has ever seen.” Artz documented some of the failures of the Oakland City Council’s recently adopted anti-graffiti ordinance, noting that no fines have been levied against illegal vandals to date, while property owners in tagging hotspots in West and East Oakland are subject to fines from the city, unless they abate tagging within a specified time period.

While Artz identified property owners—many of whom supported the anti-graffiti ordinance, not realizing its passage would result in increased financial liability for them—as victims of this epidemic, he also blurred the line between the vandals causing the property damage and muralists offering a solution by covering blighted walls with artwork.

This mural was commissioned by local property owner Bill Vidor as an alternative to ongoing vandalism. Over a year later, it remains untouched.

Artz notes the only people offering property owners “protection” are muralists, yet this practice was framed as extortion, based solely on one interview with a tagger who is also a muralist. This claim seems sensationalist and slanted; in CRP’s experience, we have worked with community organizations, Community Benefit Districts (CBDs), and property owners. None have been extorted.

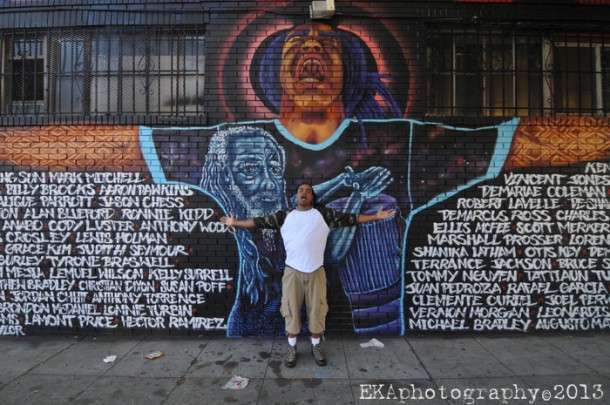

In the past three years, CRP has painted over 100 murals in Oakland. Our recent work includes a mural dedicated to food justice at the People’s Grocery headquarters on 7th St. in West Oakland, the “Stop the Violence” mural at 60th and Macarthur – a hotspot in the deadly zone known as “Sem City” – and the “Who Stole the Sun” mural at 20th and Telegraph, the site of a murder following Oakland’s popular First Friday event. These efforts have helped to uplift the community and increase a sense of neighborhood identity, while also offering measurable blight reduction.

Foreclosed and abandoned properties attract blight in all its forms. Murals have proven to be a cost-effective deterrent to vandalism.

CRP has also been approached by business owners to paint murals after they reported tagging on their property and were threatened with excessive fines by the city. Currently, we are working with City Councilperson Lynette Gibson-McElhaney and property owners to enact more murals in tagging hotspots in downtown Oakland.

Murals, and by extension, muralists, are clearly not the problem. In actuality, they are the solution.

In fact, murals are part of a long-term abatement strategy to reduce tag recidivism the city formerly employed prior to the elimination of its Redevelopment Agency, which funded projects by CRP and other public muralists. And the Oakland City Council has reportedly set aside $400,000 for mural projects, although not a single mural has been commissioned out of that fund yet. Moreover, this past July, Tribune columnist Tammerlin Drummond wrote an article which made the case for public murals as a solution to “desolation,” while noting that mural artists have struggled to replace the loss of redevelopment funds.

An unheeded notification of blight on a foreclosed property speaks to the ineffectiveness of current abatement strategy.

“Who is really extorting victims of vandalism? One could argue that the city’s public works agency, which levies the fines against business owners, fits that description. In 2011, the city’s code enforcement department received a scathing grand jury report, which found widespread corruption, including discriminatory and uneven enforcement practices.But the real culprit is the abatement model itself, which is cost-inefficient and impermanent.

Here’s what we know: The city of Oakland spent over 1 million dollars in fiscal year 2011-12 for graffiti abatement, all of it on public property. Since private property isn’t included in this number, the actual abatement costs in Oakland were significantly higher, although nearly impossible to track. In the Tribune article, business owner David Perez estimates his annual abatement costs were around $6,000, while the average cost of a small storefront mural was estimated at $1,000.

Blanche Richardson’s Marcus Bookstore was threatened with a $2,000 fine from the City of Oakland until CRP protected this local treasure by painting a free mural for them.

It doesn’t take a math whiz to see that murals offer significant cost savings over the abatement model, and can provide inspiration and a source of community pride at the same time.

Abatement workers employed by the city admit they are overwhelmed by the amount of tagging they encounter on the streets. One worker confided to CRP that he often has to pick and choose who he targets for the buff, and said that more murals on public property would make an impact on at-risk areas for tag recidivism.

Oakland abatement staff say they can’t keep up with the prolific vandalism.

The core issue here is that the abatement model has been institutionalized into an outmoded, regressive, overly expensive industry which squeezes American cities to the tune of $17 billion annually. Anti-graffiti consultants—many of them former law enforcement employees–and private contractors habitually receive contracts ranging from the high hundreds of thousands to the low millions. They typically advocate for zero-tolerance policies based on an adaptation of the “Broken Windows” theory. Yet they have produced no longitudinal results. Abatement subcontractors have also proven to be cost-inefficient, and in some cases, corrupt. In San Jose, an abatement subcontractor was caught inflating clean-up costs, and in Gardena, another subcontractor was arrested for writing graffiti surreptitiously and then charging the city to clean it up.

- An abatement worker buffs tags from a wall.

Oakland makes a great case study: Its graffiti ordinance was the work of former Councilperson Nancy Nadel. At hearings around the ordinance, several speakers–including a coalition of mural organizations, business owners, and at least two Councilpeople– expressed reservations that the ordinance was unenforceable and victimized business owners a second time. The City Attorney admitted there were no provisions for restorative justice as outlined in the ordinance.

While Oakland hasn’t fulfilled its own mandate for including a restorative justice component to its abatement practices, CRP created this “Silence the Violence” mural led by youth from Oakland Unity High School, as part of a preventative model.

Yet the ordinance was passed as a parting gift to Nadel for her many years of civic service, despite the Council’s reservations. Several months into its existence, the failure of the anti-graffiti ordinance to do any kind of enforcement —other than against property owners— means that the promised victim’s compensation fund, which theoretically allows business owners to recover their abatement costs, exists in name only. Meanwhile, tagging in Oakland is reportedly up by as much as 60 percent, with the recent surge attributed to mostly white hipsters and non-residents. The new tagging trend has even been equated with the encroachment of gentrification.

The reality is that there is no way to completely eliminate graffiti. But we need sounder, smarter policy around how abatement is implemented. Unoccupied, bank-owned foreclosed homes, which are magnets for not only tagging but illegal dumping, drug use, and prostitution, could be muralized, stabilizing property values while beautifying neighborhoods in disrepair. Mural diversion programs for juvenile offenders which employ restorative justice principles can strengthen communities while creating career track options for wayward youth. Public-private partnerships can take a major bite out of blight with long-term results. Mural campaigns can restore neighborhood identity, or promote sustainable, healthy community development initiatives. All of this is possible with a forward-thinking approach to blight mitigation. But to do that, we need to stop equating legitimate public art with vandalism, and stop conflating credible mural organizations with extortionists.

2 comments