This CRP mural in Old Oakland honors the workers of Local 20

Last November, then-Councilmember Libby Schaff proposed a new ordinance which required a percentage of new development–.5% for residential property, and 1% for private development—for “public art.” The ordinance further codified an existing public art program, which provides 1.5% of capital improvement projects to “commission and acquire public art.” Yet while the existing public art fund is administered by the city’s Cultural Arts dept., the new ordinance “provides developers with the option of commissioning public art on the development site or making an in-lieu contribution” to the existing fund.

In other words, it essentially makes developers curators—who can make the decision to commission art onsite on new developments, with no community review process. Furthermore, the art commissioned can be installed in the lobbies of buildings and locations only accessible to the public during business hours, which changes the definition of what muralists, artists, and many in the community would consider “public” art.

This water dragon mural in Chinatown honors cultural diversity and neighborhood identity

Indeed, it’s unlikely the ordinance will significantly impact Oakland neighborhoods which are “arts deserts,” as artist Caroline Stern speculated in an SF Chronicle article. That’s because much of the new development in Oakland is centered around the Uptown/Downtown district, which boasts the city’s greatest concentration of art galleries as well as numerous murals and existing public art installations such as the sculpture in the park next to the Uptown Apartments. Other upcoming development projects are located on Grand Ave. near Lake Merritt, and the Fruitvale Transit Station, neither of which are in the city’s most art-poor regions.

While the ordinance ostensibly has good intentions – it purportedly “enriches Oakland’s visual environment, integrates the creative thinking of artists into public construction project, and provides a means for citizens and visitors to enjoy and experience cultural diversity” – it outlines no criteria for selecting or prioritizing art, nor does it define cultural diversity in any specific terms.

This $600,000 installation at 17th St.’s BART is an example of the kind of public art favored by developers

While some developers have bristled at the ordinance, calling it a new tax, community art advocates have charged that the ordinance essentially privatizes public art and could accelerate gentrification, excludes the arts community at large from the drafting process, is poorly-thought through, and could be poorly-implemented. Although the new ordinance does thankfully require that artists selected be Oakland residents, it could result in a slew of vanity projects, mainly in rapidly-gentrifying areas, which don’t meet the actual needs of the community for public art, i.e., as part of beautification efforts in blighted areas.

Blighted neighborhoods bombed by taggers are unlikely to be significantly impacted by Oakland’s new Public Art ordinance

Few new developments, if any, are planned for the city’s most-blighted neighborhoods, in which the proliferation of graffiti tags are the only visible symbol of public art. And while the proposed Coliseum City plan could stimulate development in long-neglected sections of East Oakland, the plan is in jeopardy of not happening, according to a recent Oakland Tribune article. The ordinance also doesn’t affect development projects begun before the new requirements went into effect, such as the 3,100-unit Brooklyn Basin project.

Furthermore, promises from now-Mayor Schaff made back in November that it would be possible to amend the ordinance—a pledge made in exchange for community arts advocates not mounting more vocal opposition at the time of the Council vote—may not have been earnest.

At a recent “stakeholders” meeting with arts advocates, city staffers, visiting officials from Emeryville and San Jose, and a representative from the development community, both the Mayor’s representative, Shereda Nosakhare, and Scott Miller, from the city’s Zoning Department, indicated that significantly amending the ordinance to further prioritize the in-lieu contribution (which would at least place the curator’s job in the hands of experienced city staff) and allow for more community input on what kind of art can be commissioned, would not go over well with developers. The city, Miller said, “can’t create an implementation program which is so burdensome.”

This West Oakland tribute to a 3 year-old victim of gun violence was sadly vandalized and has not been repainted.

It remains to be seen whether developers, in their curatorial role, will select projects and artists which are truly emblematic of Oakland’s cultural arts community and actually embody the cultural diversity alluded to in the ordinance’s wording. But in all probability, we may end up with more projects like the $600,000 installation at the BART walkway in-between 17th and 18th Sts., instead of the vibrant and colorful murals which uphold community pride and inspire viewers like the “Waterwrites” mural on Broadway (painted by the Estria Foundation), the “Oakland Is…/ West Side Is The Best Side” mural (painted by Vogue and Bam TDK) on Peralta, or the Alice St. Mural (painted by CRP), to name three much less-costly public art projects.

Jerri Lange and Chauncey Bailey are among those honored on CRP’s Alice St. mural

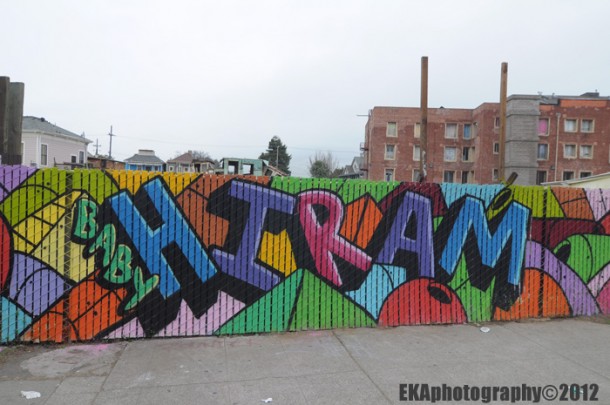

The community needs for public art are evident in the city’s grittier, grimier parts of town, such as the 7th St. strip in West Oakland–which has become a haven for taggers, to the detriment of the community: a mural honoring Baby Hiram, a child victim of gun violence, was vandalized and has not been repainted, due to lack of funds. It is CRP’s belief that projects like this should be priorities of a public art fund.

Yet most developers aren’t Oakland residents, and either don’t know or don’t care about the city’s history, its neighborhoods, or its culture. It’s a stretch to expect them to be recognizant of community needs for cultural art. So it seems disingenuous to give them total control over determining what is supposed to be public art, especially since the new ordinance makes no provision for selecting art with demonstrable community benefit. It’s also disappointing that Schaff would kowtow to developers while claiming to support public art, when the fact of the matter is that the community has been all but removed from having input into the process of creating the art which will arise from this ordinance.

TDK Family’s “West Side is the Best Side” was painted in a blighted section of West Oakland

In a best-case scenario, developers would either choose the in-lieu contribution option and allow the Cultural Arts Department to administer art commissions, or have some way of interacting with potential artists and engaging with community. At the stakeholders meeting, it was suggested that artist-developer meetings could be arranged through Pro Arts, a gallery located on the same block as City Hall. Needless to say, this process would likely exclude many artists and may result in a lack of cultural diversity; a more inclusive process might hold such meet and greets all over town, at venues like East Side Arts Alliance and Youth Uprising.

CRP believes that public art can and should be part of a holistic community beautification process which cultivates art corridors and helps uphold community and neighborhood identity. Unfortunately, the “Percentage for Public Art” ordinance falls far short of those goals.