Recently, Pacific Standard magazine wrote an article about public art in Oakland. Specifically, the story addressed mural brokers, middlemen who connect fat cat developers with artistic talent – for a fee. Mural brokers, the article explains, handle logistics such as price negotiations, choosing artists, prepping walls for painting, and handling insurance coverage – “everything necessary to make the mural happen except paint it.”

Dragon School’s murals have reduced blight while upholding Chinatown’s cultural identity

The article correctly points out the cultural cachet of murals, and their historical connection to illegal street art, as well as the role murals have played in community activism. It also identifies a dichotomy between the development boom, which has resulted in rapid gentrification of cities like Oakland, and an emerging trend wherein murals have become “the must-have amenity for leading real estate developers,” quoting Architectural Digest. Mural brokers are taking advantage of new opportunities to valuate public art, but in doing so, they may also be advancing a pro-growth agenda which is effectively displacing artists and other members of what the City of Oakland’s Cultural Affairs department refers to as the Arts & Culture Economy.

In the Cultural Plan released by the City in September, it’s reported that almost half of Oakland’s artists have experienced displacement of their living and/or studio spaces, mainly due to rising rents. The irony of this is that Oakland’s development boom coincided with an arts-driven cultural renaissance which reshaped the image of the city and brought national attention to its arts, culture, and nightlife scene. Placing a mural on a formerly-blighted wall exchanges neglect with vibrancy, but also raises property values, and in some cases, has attracted developer interest, resulting in an upward spiral of market-rate rental units. Between 2010 and 2015, rents in Oakland skyrocketed 76%, making it increasingly difficult for low-and middle-income residents—a category which includes most public artists—to afford to live in Oakland.

Downtown’s development boom has further accelerated gentrification in Oakland.

Public art, as a practice, goes back to the earliest days of human civilization—cave paintings and hieroglyphics—and will likely continue to exist as long as there are walls which can be written or painted on. While illegal street art will always be an avenue for expression, for public art to be sustainable for artists means that artists have to be able to make a living creating it.

Muralist collectives and arts organizations are intrinsically-identified with the communities they serve; mural brokers only come into the picture when there is big money to be made from developers or corporate entities. On one hand, for-profit mural brokers allow muralists to just concentrate on their art without also having to keep track of logistics. But on the other hand, they create a buffer between patron and artist, may result in exclusionary practices, and may undermine the thorough community engagement practices developed by non-profit arts organizations—including CRP, as well as Trust Your Struggle, Dragon School, East Side Arts Alliance, and Attitudinal Healing Connection. These organizations have all upheld the tradition of the community mural movement, which has embraced social and political expression, and seeks to give ownership of the mural to the community it resides in.

CRP’s “Universal Language” celebrates the cultural resilience of at-risk populations.

The Pacific Standard article revolves around the Athen B. gallery and its mural brokerage model. But Athen B. isn’t the only mural broker in town. Visit Oakland has at times served as a mural broker, lining up gigs paid for by the Marriott Hotel and the Oakland A’s. Another model is 1AM’s, which combines a gallery/art supply store with an art agency, and offers among its services “art experiences” – which include graffiti, street art, and “Golden Age of hip-hop” workshops – but also team-building exercises directed at corporate clients. This isn’t necessarily a bad thing, as it can break down the walls framing public perception of aerosol art as inherently illegal, while creating investment in the creative economy. But’s it’s also not necessarily a good thing, as it may trivialize cultural and aesthetic practices. What all three models have in common is they are banking on the commodification of public art.

The danger of for-profit entities in this role of middleman is a dilution of community values or even outright censorship which advances gentrification, erodes cultural identity, and may result in further economic inequity and forced obsolescence for community-based artists and organizations which aren’t part of a mural broker’s artist roster.

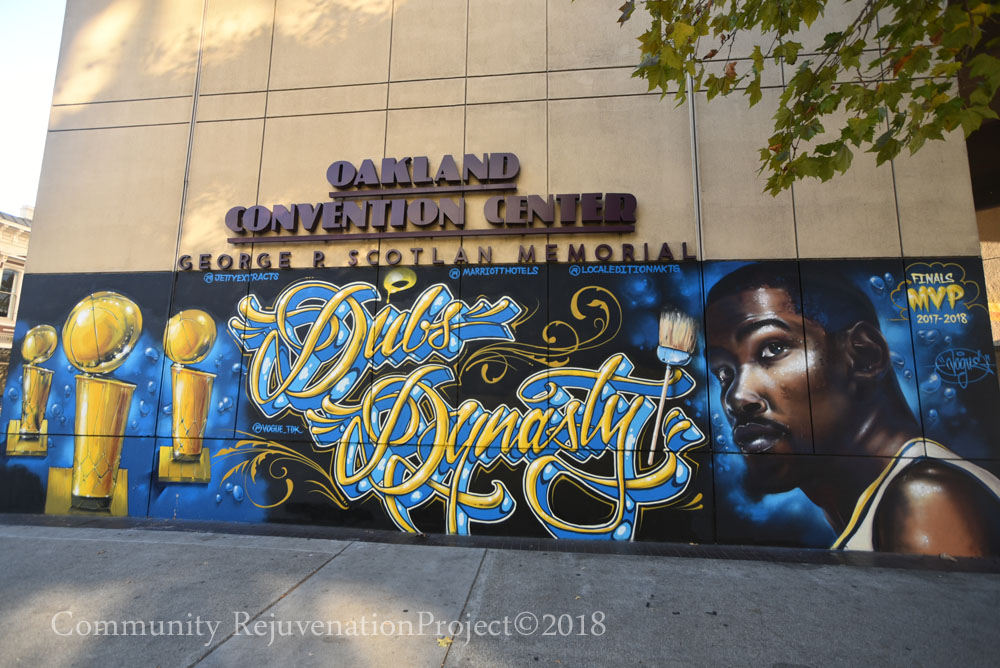

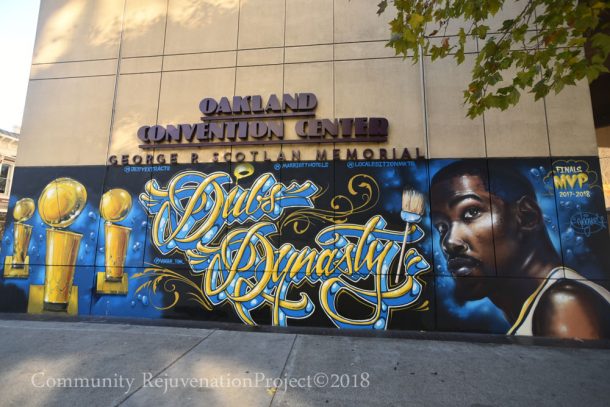

This massive mural is essentially an ad for a marketing campaign.

The Athen B. model, for instance, bypasses the Request For Qualifications/Call For Artists which is standard practice for many mural commissions. But it also omits any criteria around community engagement, i.e. community input into the images going into the community — a major point of emphasis for non-profit artist organizations.

The murals brokered by Visit Oakland are visually-stunning, yet their content comes down to marketing campaigns for the A’s and Warriors, or a tourist-friendly collage of imagery which lacks any real connection to Oakland’s community mural tradition and values. Some mural brokers emphasize abstract art which isn’t without aesthetic appeal, but may not incorporate specifically-cultural aspects, or be apolitical in tone.

“The danger of for-profit entities in this role of middleman is a dilution of community values or even outright censorship which advances gentrification, erodes cultural identity, and may result in further economic inequity and forced obsolescence for community-based artists and organizations which aren’t part of a mural broker’s artist roster.”

The contrast between these models and that of the non-profits is stark. CRP’s “Universal Language” mural, for instance, was specifically inspired by Afro-Diasporan and Pan-Asian cultural practitioners. Trust Your Struggle’s recent mural inside the Greenlining Institute’s building resonates with the resistance and resilience of ethnic populations; Attitudinal Healing Connection’s “Superheroes” series was developed with input from Oakland schoolchildren. ESAA’s murals in the San Antonio district continue the legacy of the Chicano Movement and the Mexican mural movement associated with Diego Rivera. And Dragon School’s Chinatown murals have reaffirmed the distinctly Asian identity of that neighborhood.

This Warriors mural looks great, but exemplifies the corporate commodification of public art.

While private developers have the right to put anything they want on buildings they own, there is also a precedent established by the Community Coalition for Equitable Development of garnering community input into art required by the Percent For Art Fee, which has included the creation of art advisory boards and even investment into nearby cultural institutions. These practices align with the Cultural Plan’s framing around cultural equity as a guiding concept.

Yet there is nothing in the mural broker model which specifically incorporates cultural equity as a value. Indeed, the mural brokers may ultimately undermine all the work non-profit arts organizations have done for decades – or simply allow developers to bypass commissioning these organizations altogether.

While its exciting and interesting to see new murals proliferate in Oakland, there are real concerns about mural brokers’ models and whether they can be adjusted to incorporate community values and uphold cultural equity. It’s possible that some developers may want art which does reflect these values, but it’s far more likely that images which reflect populations at risk of displacement will be sanitized, in favor of less-provocative or socially-unconscious images.